The Best Way To Predict The Future Is to Create It.

Innovation II: What separates builders who compound into the future from those who end up repairing the past.

Before we dive in, a quick announcement from our side:

Kirsty Nathoo - former GP and CFO of YCombinator (2010–2024) - is joining Studio Alpha as an advisory board member.

We’re incredibly proud to have her with us. Meet Kirsty and several of our board members at the Studio Alpha Jam on December 10 at Cooley.

If you want to understand innovation, start with one simple comparison.

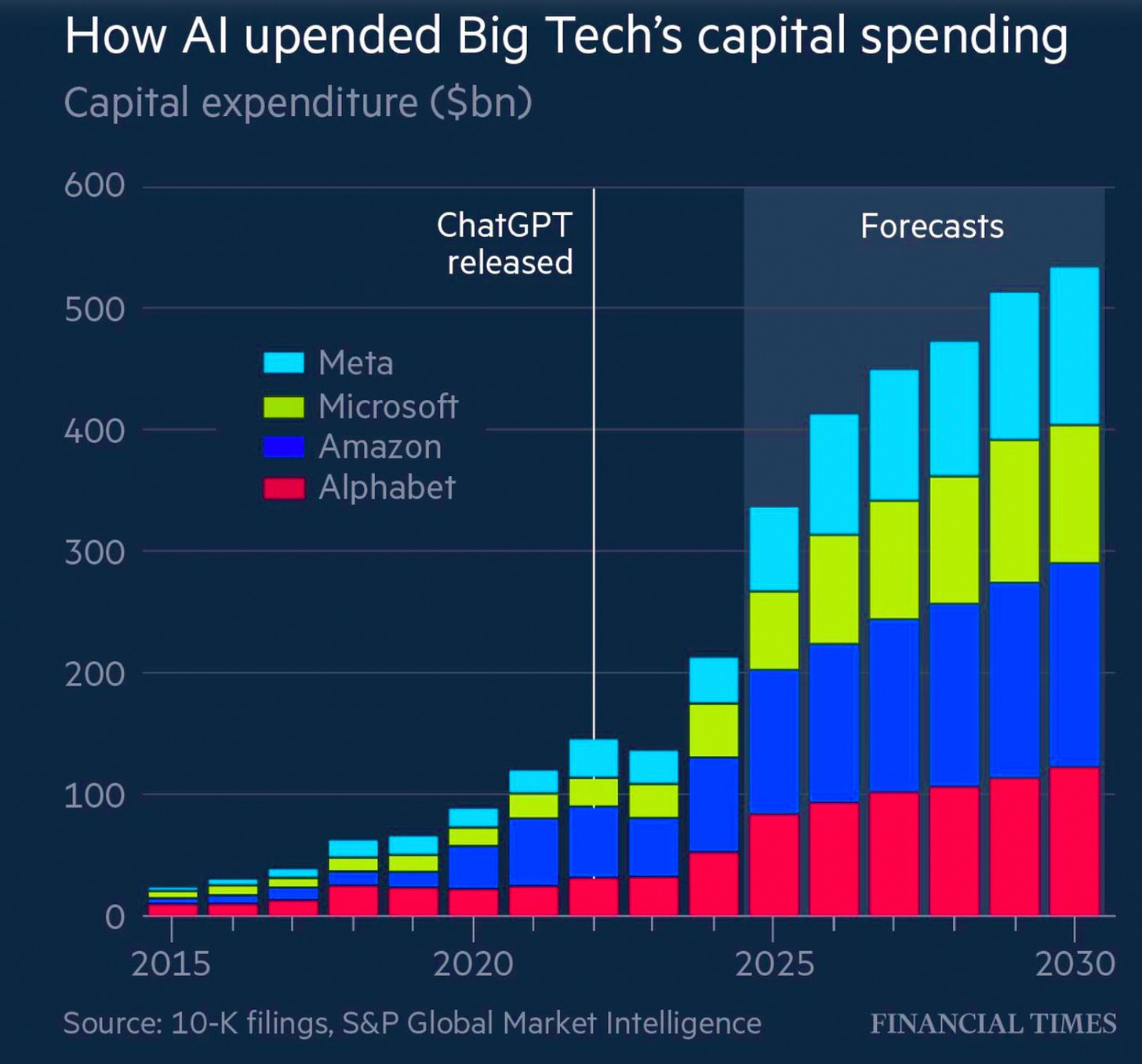

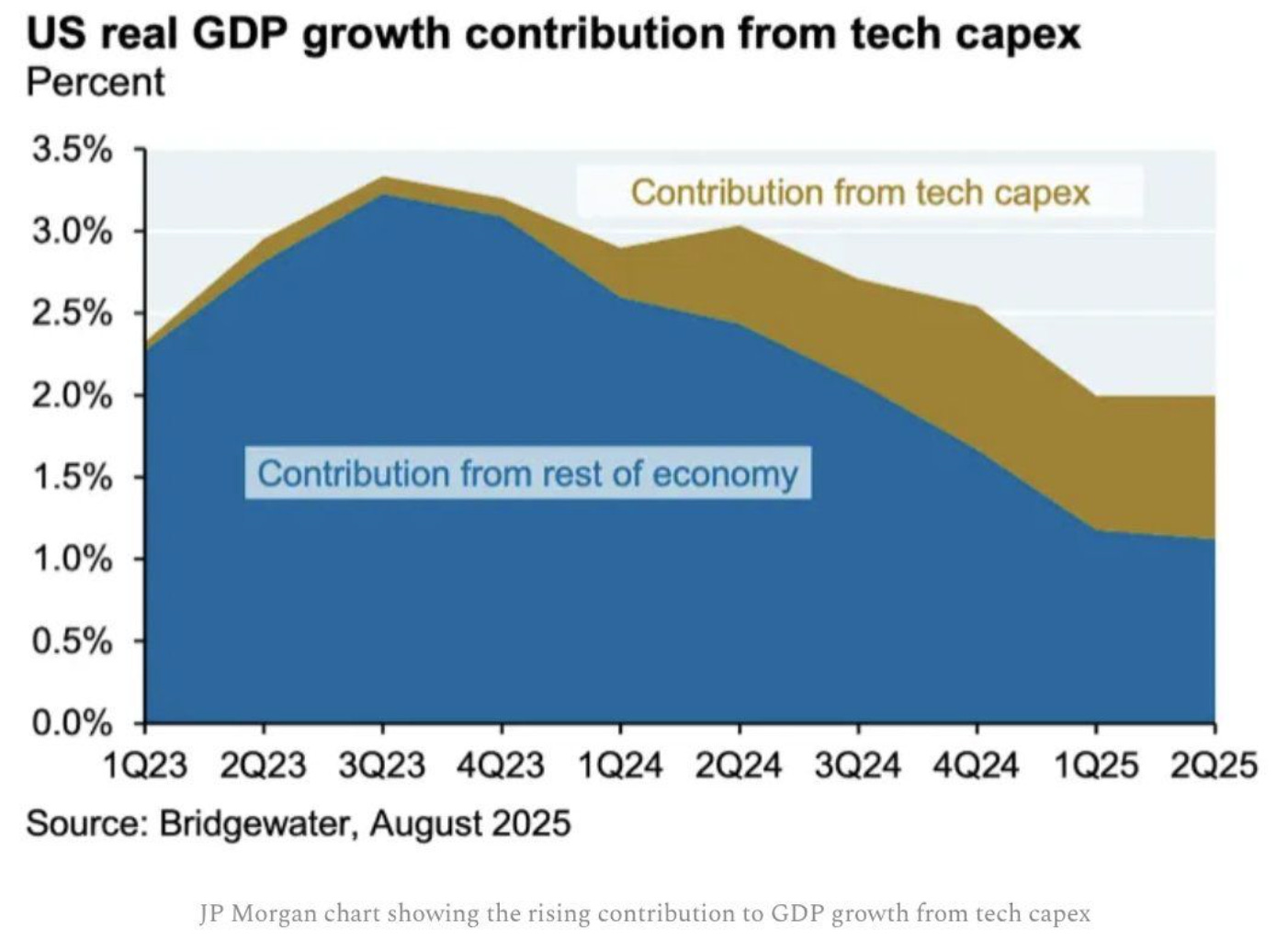

Over the next two years, the West Coast hyperscalers - Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta - will invest half a trillion dollars into datacenters, chips, and AI infrastructure.

Germany - one of the richest economies in the world - will also invest half a trillion dollars into bridges, rail networks, energy grids etc..

Same number.

Completely different direction.

And that contrast tells you everything you need to know about WHAT innovation actually is.

Why do some systems compound forward while others fight decline?

Why do some founders catch the next wave early, while others react only when it’s already too late?

What separates hyperscalers from institutions that once led the world?

It’s not talent.

It’s not money.

It’s not luck.

This chapter is about what innovation really is — not the buzzword version, not the corporate version, but the one we see every day with founders who build the future.

Let’s break it down.

1. When Innovation Becomes Maintenance: Germany vs. the West Coast Hyperscalers 🏄🏽♀️

In the next two years, the four Western hyperscalers - Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta - will collectively invest over $500 billion into AI-driven data centers, semiconductor capacity, renewable energy integration, and global cloud infrastructure.1

This number is real and well-documented: Microsoft alone committed $50 billion per year, Amazon over $55 billion, Google $30-35 billion, and Meta ~$35 billion annually into capex and AI infrastructure.2

In total:

🥤 Hyperscalers → $500 billion in 2 years → into the future.

Now compare that to Germany, one of the wealthiest nations in the world aka “the locomotive of EU”. Good luck:

Germany 🇩🇪 plans to invest €481 billion over the next TWELVE years (not two) simply to repair collapsing bridges, aging rail networks, underbuilt energy grids, outdated public IT infrastructure, and deferred maintenance across nearly every sector.

In total:

🍺 Germany → ~€500 billion in 12 years → into the past.

Into repairing what was neglected for 20 years. Same number. Completely different meaning.

This contrast is not about politics or national pride. It is a live demonstration of WHAT innovation is - and what happens when you stop doing it.

Germany is not failing because Germans are not smart, or hardworking, or creative.

Germany is failing because it did not invest in innovation early enough, and now must invest the same amount of money merely to prevent decline.

This is the essence of Chapter 1:

Innovation is not “nice to have.” Innovation is what keeps societies on the right side of compounding forces. If you don’t invest ahead of time, you pay an order of magnitude more later - just to stand still.

🥤 The West Coast hyperscalers invest in new capabilities:

🍻 Germany invests in fixing the past:

One system invests to lead the next era.

The other invests to avoid collapse from the previous era.

This is not a moral judgment. It’s mathematics.

When you invest in innovation early → you compound.

When you don’t → you decay.

And once decay begins, the cost of catching up becomes exponential.

This is exactly what Schumpeter meant when he said that capitalism survives through “creative destruction” - continuous renewal from the inside.

If you skip the renewal phase, destruction comes without creation.

Germany’s situation is the case study of a system that optimized yesterday’s stability at the cost of tomorrow’s renewal. The hyperscalers are the case study of a system that does the opposite: they destroy their own business model before someone else does.

If we want to understand WHAT innovation is, we must first understand what happens when innovation stops.

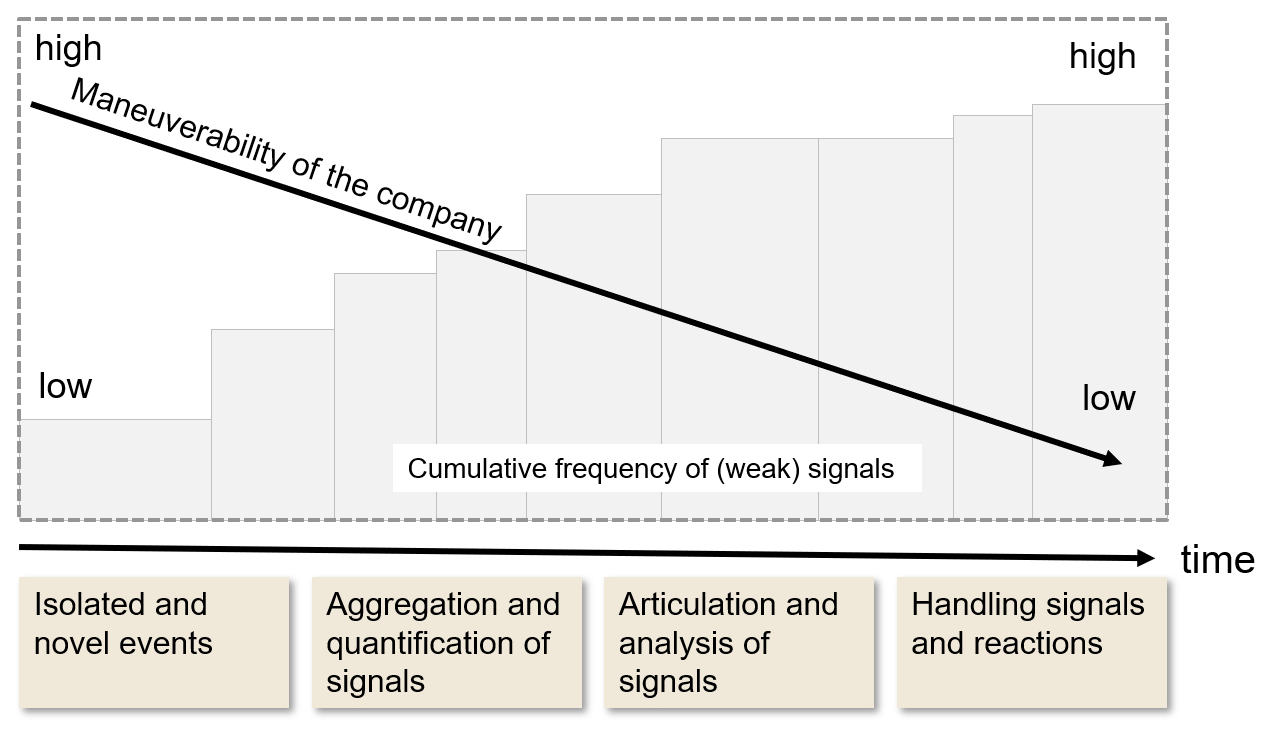

2. The First Capability: Weak Signals

This is the skill of sensing weak signals3 - an idea introduced by Harry Igor Ansoff in the 1970s, long before anyone talked about disruption or exponential curves.

His insight was simple:

The future always shows up quietly before it shows up loudly.

Every major shift begins as noise:

a strange user behavior,

a tiny anomaly in a dataset,

an academic paper almost nobody reads,

an early prototype that barely works,

a complaint from an unexpected customer segment,

a technology curve bending faster than expected,

a workaround users repeat even though it’s painful.

Weak signals are the earliest, faintest indicators of what the world will care about next.

Most people ignore them because they don’t look like data.

They look like inconvenience.

They look like edge cases.

They look like nonsense.

Founders who see and act on weak signals build the future.

Incumbents who ignore weak signals get disrupted by it.

Let’s walk through examples founders actually feel.

Netflix (2007): The Bandwidth Whisper

In 2007, broadband penetration was low.

Streaming barely worked.

DVD-by-mail was still printing money.

Netflix saw bandwidth creeping upward — not enough to justify a full pivot, but enough to signal that viewing habits would change.

While Blockbuster optimized store traffic and late fees, Netflix built streaming.

By the time the infrastructure existed, Netflix already owned the market.

Weak signal sensed → opportunity seized → world realigned.

Figma: Multiplayer Before Anyone Wanted It

Most designers in 2015 were still using local files.

Cloud collaboration felt unnecessary — even risky.

But Figma saw something subtle:

teams were already trying to collaborate by email, Dropbox, screenshots, Slack attachments — all painful, manual workarounds.

These workarounds were the weak signal.

Where users tolerate pain, a new product category waits to be born.

Figma built multiplayer design years before Adobe understood the threat.

By the time Adobe woke up, the next generation of designers had already moved.

Uber: Mobility Inefficiency Invisible to Data

City transport systems looked “fine” on spreadsheets.

Taxi companies were profitable.

Regulators considered the market stable.

But Uber noticed the weak signals:

long wait times,

inconsistent prices,

taxis clustering in the wrong places,

consumer frustration that didn’t show up in official stats.

Uber didn’t invent mobility.

They solved for the job-to-be-done long before data confirmed the demand.

Apple: Multi-Touch as a Future Behavior

Before 2007, nobody asked for multi-touch.

Nobody wrote in surveys:

“Please give me a phone with glass I can tap.”

But Apple noticed the tiny cracks:

stylus frustration,

hardware keyboards limiting UI evolution,

user experiments in early human–computer interaction research,

touch sensors becoming cheaper.

These were weak signals — faint, but directional.

Apple acted.

Nokia didn’t.

The rest is history.

YouTube (2005): Building Before the World Was Ready

The first YouTube video — “Me at the zoo” — is not iconic because of elephants.

It’s iconic because YouTube was built before anyone had the bandwidth to upload videos.

Pic. YouTube’s first video: ‘Me at the zoo’ (2005). Co-founder Jawed Karim talks about elephants

In 2005:

home broadband was slow,

video codecs were weak,

mobile didn’t exist,

cameras were bad.

But Jawed Karim and the team saw a simple weak signal:

people wanted to share moments, even if infrastructure made it painful.

They built anyway.

The world caught up later.

Weak signal → bold bet → category creation.

What Founders Miss About Weak Signals

Weak signals never come with certainty.

By the time you have certainty, you’ve already missed the timing.

Founders often ignore weak signals because:

they look too small,

they don’t fit current priorities,

they don’t justify a budget,

they feel “off-road” compared to the roadmap,

nobody else believes in them.

But the irony is:

The earlier the signal, the bigger the opportunity — because nobody else sees it yet.

Weak signal sensing is uncomfortable because it forces founders to bet before validation.

This is the emotional opposite of corporate governance.

It’s also why weak-signal sensitivity is rare — and valuable.

Founders who train this muscle:

talk to users more,

stay close to the edges of behavior,

read academic papers,

follow developer communities,

observe early adopters,

watch anomalies,

and take small experimental bets early.

Weak signals don’t guarantee success.

But ignoring them guarantees irrelevance.

The Founder Takeaway

Weak signals are not data.

They are invitations.

Invitations to explore.

Invitations to rethink.

Invitations to build something the present isn’t demanding yet — but the future will.

If absorptive capacity helps you understand today,

and dynamic capabilities help you act on what’s changing,

weak signal sensitivity helps you see tomorrow before others do.

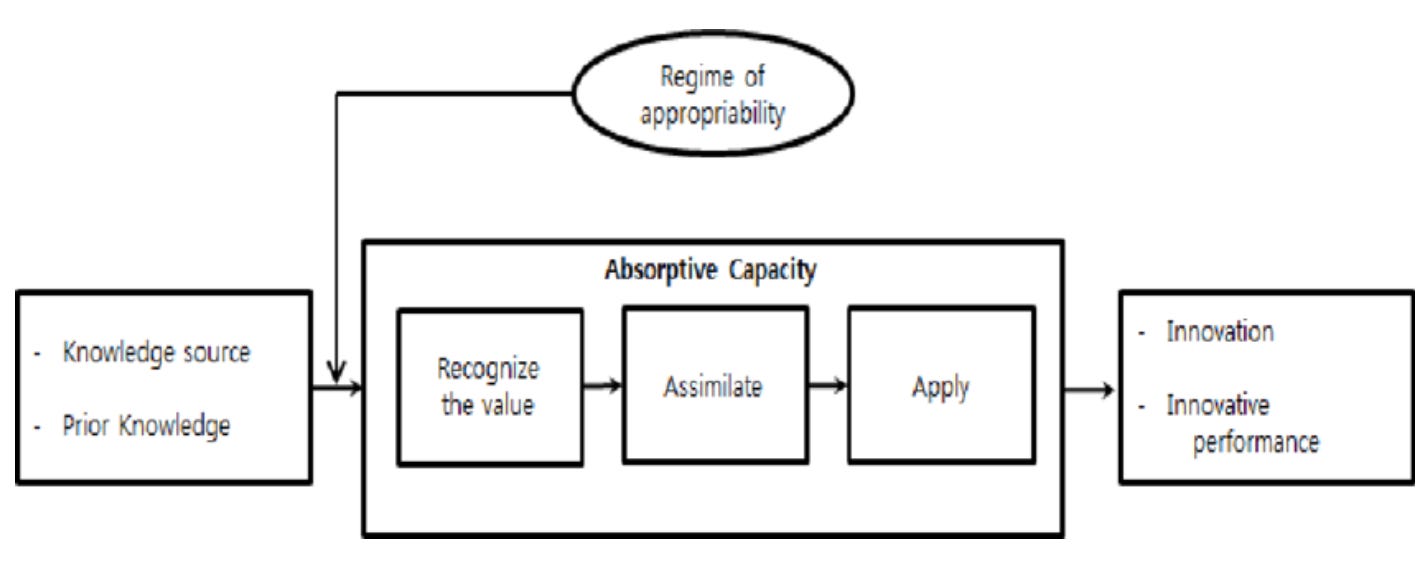

3. The Second Capability: Absorptive Capacity

So the obvious question is:

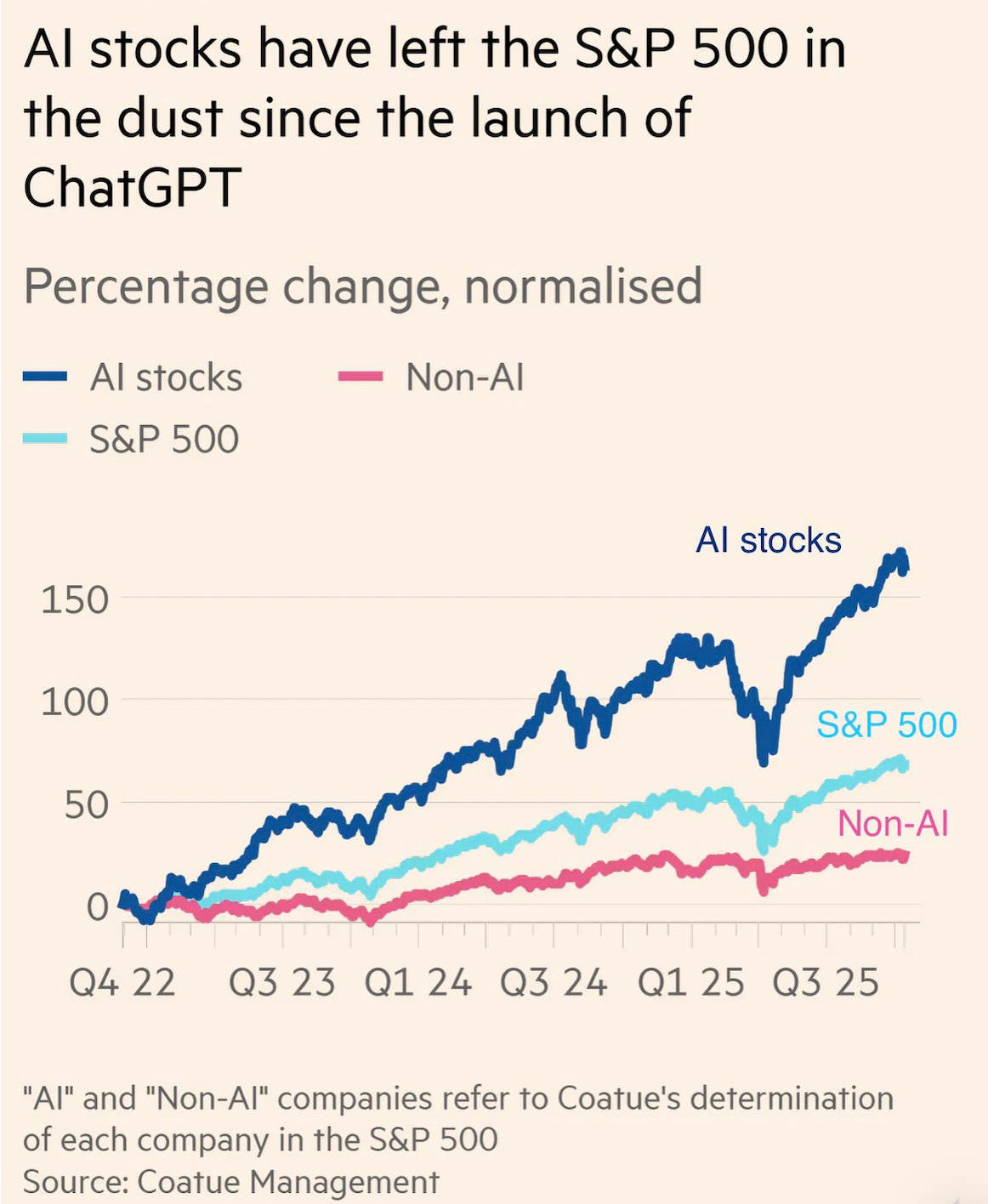

Why do the hyperscalers see the future early - while others only react once it’s already here?

It’s not culture, politics, or money.

It’s capability.

The second capability - and the one most founders underestimate - is absorptive capacity: the ability to recognize, digest, and apply external knowledge faster than competitors.

The idea comes from Cohen & Levinthal (1990).4 Long before LLMs, GPUs, or startup ecosystems existed, they made one simple observation:

Your ability to innovate tomorrow depends on what you learned yesterday.

Not how creative you are.

Not how many ideas you have.

Not how motivated your team feels.

It’s whether you can absorb new insights from the outside world quickly enough to act on them. This is why “building in a cave” kills startups. Isolation is the enemy of innovation. Founders who refuse external input don’t stay “focused.” They stay blind.

Absorptive capacity explains some of the biggest strategic divergences in tech:

NVIDIA vs. everyone else

While most of the industry dismissed deep learning as academic hype, Jensen Huang saw early research signals, understood their trajectory, and reoriented NVIDIA years before demand arrived.

Today, NVIDIA is the AI compute industry.

OpenAI vs. Google

Google invented the transformer architecture - but OpenAI absorbed it faster.

OpenAI turned academic insight into an industrial revolution; Google hesitated inside its own structures.

Stripe vs. banks

Stripe mastered global fintech regulation in a fraction of the time banks spent debating governance.

The banks had 100 years of head start - Stripe had better absorptive capacity.

BlackBerry vs. the world

BlackBerry saw multi-touch, saw apps, saw consumers shifting…

and dismissed all of it.

They didn’t fail because they lacked talent - they failed because they didn’t absorb weak external signals.

Absorptive capacity is not a personality trait.

It’s a system inside the company:

scanning

learning

synthesizing

integrating

acting

Companies with strong absorptive capacity evolve with reality.

Companies without it eventually break when reality evolves without them.

And for founders, the lesson is simple:

Innovation begins long before you build something new.

It begins the moment you decide to learn faster than the world is changing.

See also our Blog to “Absorptive Capacities” here

3. The Third Capability: Dynamic Capabilities

If absorptive capacity is about seeing the world correctly, then the third capability is about moving - about changing direction faster than the environment around you. This is what David Teece famously called dynamic capabilities, and it remains one of the most useful ideas ever written for founders.5

Teece breaks it down into three verbs:

Sensing → Seizing → Reconfiguring

It sounds academic, but founders live this every day.

Sensing

Seeing opportunity - before the data proves it.

Understanding customer behavior not by surveys, but by intuition sharpened through exposure. Recognizing when a technology curve is bending, or when a market window is opening.

Every founder thinks they’re good at this.

Most overestimate it.

Seizing

This is the part most startups skip - not intentionally, but quietly.

Seizing means deciding:

“This is relevant for us, and we will commit.”

Commit time.

Commit people.

Commit money.

Commit to changing what you’re working on next week.

And commit before competitors understand what’s happening.

Seizing is where the innovators separate from the maintainers.

Reconfiguring

This is the hardest part - and the part that kills most companies.

Reconfiguring means reshaping your company - teams, priorities, processes, even identity - to fully exploit the opportunity you sensed and seized.

Most organizations can see an opportunity. Some even move toward it. Almost none can change themselves fast enough to capture it.

This is why dynamic capabilities matter more today than at any point in the past 50 years.

Let’s look at real-world examples founders immediately understand.

Amazon (AWS): The Textbook Case

Amazon didn’t just sense the need for scalable computing.

They seized it by committing resources when cloud revenue was effectively zero.

And they reconfigured the entire company around AWS.

The retail business stopped being the center of gravity.

Infrastructure became the engine.

Today, AWS generates more profit than all of Amazon’s retail divisions combined.

Dynamic capabilities in action.

Tesla: Vertical Integration as Reconfiguration

Long before EV demand was obvious, Tesla sensed battery cost curves.

Then they seized control of the supply chain — mines, cells, software, charging.

And they reconfigured the automotive production model around vertical integration.

German OEMs are still debating this shift inside committees.

Dynamic capabilities don’t wait for consensus.

They act long before consensus is possible.

Airbnb: Reconfiguring Global Travel

Airbnb didn’t build a new hotel system.

They sensed a latent demand — flexible lodging.

They seized the opportunity through supply-side onboarding.

And they reconfigured the economics of accommodation worldwide.

Hotels saw it, but could not reconfigure their asset-heavy, centralized model.

SpaceX: Reconfiguring Rocket Economics

SpaceX sensed what the incumbents ignored:

launch costs were unsustainable.

Pic. SpaceX launches more Starlink satellites into orbit, recaptures Falcon 9 rocket on November 18, 2025

They seized the opportunity by betting on reusability.

And they reconfigured the industry’s economics — literally landing boosters on barges — forcing NASA and every global space agency to rethink procurement.

This is dynamic capability at industrial scale.

Microsoft: The Most Elegant Pivot in Tech

Under Satya Nadella, Microsoft sensed the shift to cloud and developer ecosystems.

They seized it by prioritizing Azure over Windows — a political nightmare internally.

And they reconfigured the entire company around cloud-first architecture, partnerships, and open systems.

Today Microsoft is one of the strongest AI platform companies in the world.

Dynamic capabilities are not magic.

They are decisions.

The Founder’s Version

For founders, dynamic capabilities are the difference between:

building the same product for too long

vs. shifting when the world shifts

vs. shifting before the world shifts

A startup that can’t reconfigure dies the moment the market changes.

A startup that can reconfigure becomes a category leader.

Dynamic capabilities answer one question better than anything else:

“Can you change direction faster than the environment changes around you?”

Most companies can’t.

Startups must.

4. How the Three Capabilities Work Together

If you look at weak signals, absorptive capacity, and dynamic capabilities separately, they each explain a different part of innovation. But innovation doesn’t happen in parts. It happens when these three capabilities reinforce each other.

This is the moment where founders usually go:

“Ah, now I get how this fits together.”

Because the truth is simple:

Innovation is not one capability.

It is the interaction of three.

Absorptive capacity → You understand what is happening.

You learn faster, integrate external insights, and see reality for what it is — not what you wish it to be.

Weak signals → You understand it early.

You notice the first hints of a new behavior, a new curve, or a new need — before the trend becomes obvious.

Dynamic capabilities → You act on it decisively.

You reorganize people, priorities, and capital fast enough to actually capture the opportunity.

When these three line up — sensing, learning, acting — companies become almost impossible to catch.

You see this pattern everywhere:

NVIDIA

absorbs frontier research →

spots the deep learning wave early →

reconfigures the business into AI compute →

becomes the most important company of the decade.

OpenAI

absorbs transformer insights →

spots the weak signal (the shift from supervised to self-supervised learning) →

commits fully to scaling laws →

reconfigures around AGI vision →

creates a new category.

Figma

absorbs developer tooling patterns →

spots multiplayer collaboration early →

reconfigures product and team to bet fully on the browser →

disrupts the design industry.

Netflix

absorbs bandwidth and codec trajectories →

spots streaming when DVDs still dominated →

reconfigures entire distribution — from logistics to content →

reinvents entertainment.

Tesla

absorbs battery cost-curves →

spots the coming EV inflection →

reconfigures supply chain + software stack →

forces the entire automotive industry to change.

These companies didn’t “have better ideas.”

They had better capabilities.

Capabilities that reinforce each other:

Learn faster → see earlier

See earlier → act sooner

Act sooner → build before the world catches up

Build before → become the category

Become the category → shape the market

Most companies fail not because they lack ideas,

but because they lack one of the three capabilities:

They learn too slowly (no absorptive capacity).

They see trends too late (weak signals ignored).

They move too slowly (weak dynamic capabilities).

Miss any one of the three, and innovation becomes inconsistent.

Miss two, and it becomes impossible.

Miss all three, and you become… well, Germany in Chapter 1.

Innovation begins as sensing.

Evolves through learning.

Becomes real through decisive reconfiguration.

This is the system behind WHAT innovation is.

Not ideas.

Capabilities.

5. The Four Types of Innovation (Studio Alpha’s Framework)

Weak signals help you notice the future early — often long before the data makes it obvious.

Absorptive capacity helps you understand these signals deeply enough to act on them.

Dynamic capabilities determine whether you can actually move the organization in time.

Together, they explain why some founders feel “early but right,” while others only react once the opportunity has already become expensive, crowded, or lost.

Once you understand the three core capabilities behind innovation, the next question is obvious:

What does innovation actually look like in practice?

Innovation is not a single action.

It is the combination of four types of “newness” that companies blend in different proportions.

Founders who get this right move faster and waste less time.

Founders who don’t understand this taxonomy end up trying to reinvent the wrong thing.

Andy’s framework — rooted in Hauschildt, Kirner, and Kinkel — gives a clean, timeless structure.

Let’s walk through each type the way founders experience it.

1. Product / Service Innovation — What the customer gets

This is the most visible form of innovation.

It’s what people think about when they hear the word “new.”

Examples founders know:

Apple M1 chips — redefining laptop performance

Tesla’s heat pump and software stack — new architecture, not just new hardware

Figma multiplayer — a fundamentally different UX

Stripe Radar — machine learning layered on top of payments

ChatGPT — new interaction paradigm

These innovations change what the customer receives — and often what the market expects next.

2. Process Innovation — How value is created

This is the invisible innovation.

Most companies underestimate it.

Founders who master it build moats without realizing it.

Examples:

Tesla Gigafactories — manufacturing as a software-driven process

AWS automated provisioning — infrastructure as code

Netflix personalization engine — operationalized behavior prediction

Toyota production system — continuous-flow manufacturing

Shopify merchant onboarding — frictionless business creation

Process innovation looks boring until it becomes the thing that competitors can’t copy.

3. Organizational Innovation - How the company works

Teams, structures, culture — the things that allow a company to scale its intent.

Examples:

Amazon’s “two-pizza teams”

Spotify squads (despite the meme abuse, the principle is real)

Netflix culture deck — freedom + responsibility

Valve’s flat org — radical autonomy for creative software teams

Organizational innovation is not about posters on the wall.

It’s about designing the mechanics of how decisions get made.

Startups live or die by the quality and speed of their org decisions.

4. Business Model Innovation - How the company captures value

This is often the most powerful type — especially in SaaS and AI.

Examples:

AWS usage-based pricing — turned infrastructure into a utility

Adobe subscription shift — recurring revenue machine

Uber marketplace — matching supply & demand at global scale

Airbnb’s distributed supply model — assets without owning assets

Databricks lakehouse monetization — consumption model + enterprise expansion

Business model innovation often beats product innovation.

It changes the economics of the category.

5. How the Four Types Fit Together

Every major innovation you admire is a combination of these four layers.

Let’s take a few examples:

Tesla

Product: EV architecture

Process: Gigafactory manufacturing

Org: vertically integrated engineering culture

Business model: software + energy + direct distribution

OpenAI

Product: LLM interfaces

Process: model training pipelines + RLHF6

Org: hybrid research/product velocity

Business model: consumption-based API + enterprise integration

Uber

Product: real-time ride hailing

Process: supply-demand matching

Org: marketplace operations

Business model: transaction fee + dynamic pricing

Figma

Product: multiplayer design

Process: browser-based rendering

Org: SLT with deep product alignment

Business model: freemium + team expansion

The point is simple:

Innovation is never just a product.

It is the orchestration of four innovation types.

Founders who understand this build deeper companies.

Founders who don’t chase “features.”

6. The Startup Angle (Studio Alpha Add-On)

At Studio Alpha, when we work with teams in our Production Program, these four innovation types show up in one repeated question:

“How fast can this team adapt across product, market, process, and organization?”

In practice, this means:

discovering the market (sales, BD)

adapting the product based on real user feedback

adopting lean processes instead of premature scaling

raising capital at the right time to support the next evolution of the organization

Innovation lives across all four dimensions — not just the one founders personally prefer.

That’s why most early-stage teams need structure:

innovation is simple in theory but chaotic in execution.

Pic. “I am speed.” - Trailer Cars, 2006 (source)

7. Timing: Are You Building for Yesterday, Today, or Tomorrow?

There is one more dimension we haven’t talked about yet — and it’s the one that quietly decides whether everything in this blog helps you or comes too late:

Timing.

Hausschildt’s timing model is simple and brutal. It says that innovation decisions sit somewhere along a curve from t–3 to t+3:

t–3 – visionaries: building before the world understands the opportunity

t–2 – anticipators: committing early, before most have noticed

t–1 – early adapters: moving when the first proof points appear

t0 – synchronous: moving when everyone agrees “this is the future”

t+1 – late adapters: reacting once the shift is already priced in

t+3 – crisis mode: fixing the damage from ignoring the first five phases

Founders like to believe they’re all at t–2 or t–1.

But if we’re honest, a lot of teams operate at t0 or t+1:

They wait for customers to “ask clearly.”

They wait for metrics to be safe.

They wait for competitors to move first.

They wait for the board to be comfortable.

By the time every stakeholder feels safe, the opportunity is already crowded, expensive, and strategically uninteresting.

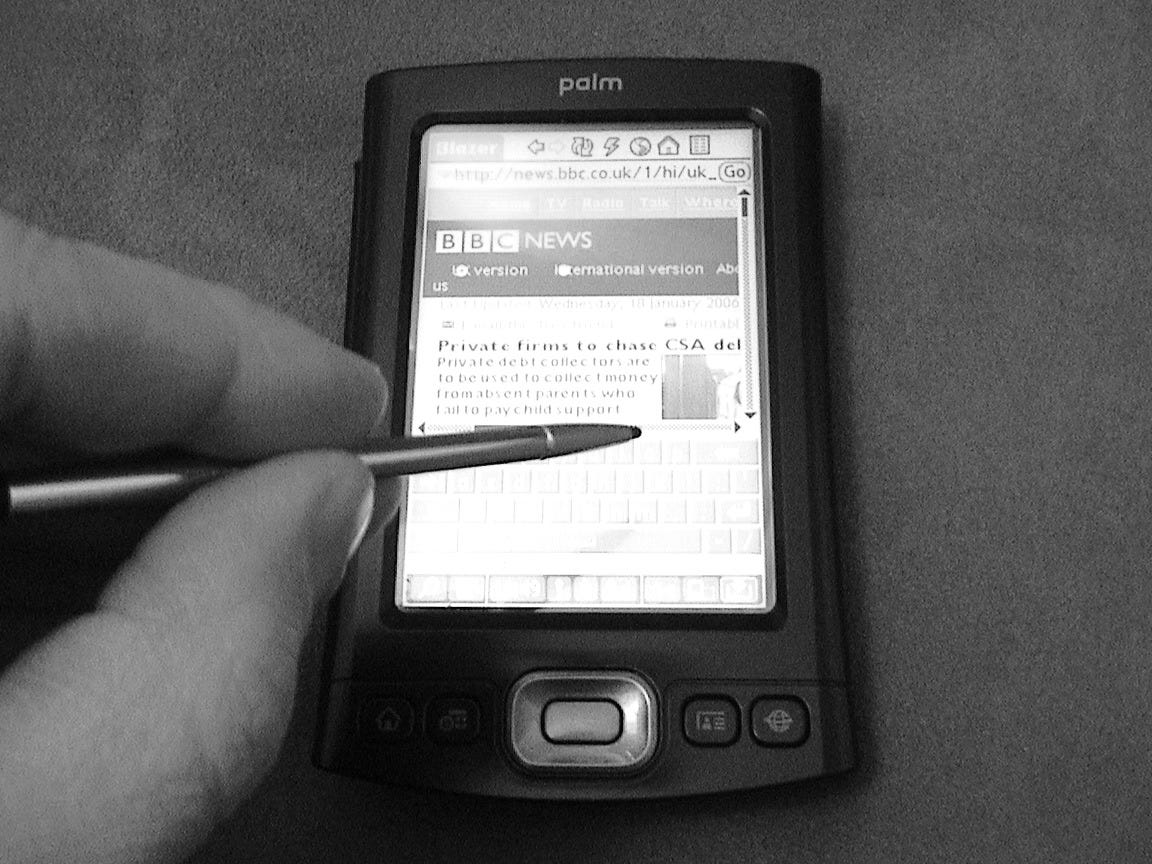

Timing is the real difference between the hyperscalers and Germany. Or Palm

The hyperscalers invest half a trillion at t–2 and t–1 — betting on AI, datacenters, and chips before society has fully processed what those bets mean.

Germany invests half a trillion at t+2 and t+3 — patching rails, bridges, power grids, and digital infrastructure after decades of underinvestment.

Same number.

Different t on the curve.

On a smaller scale, startups make the same mistake:

some act like hyperscalers,

others act like ministries.

The whole point of the three capabilities and the four innovation types is to push you upstream on timing:

Absorptive capacity pulls you away from t+1 — you see reality earlier.

Weak signals pull you away from t0 — you see the future before it’s confirmed.

Dynamic capabilities pull you away from paralysis — you can actually move.

The four innovation types give you more than one way to respond — product, process, organization, business model — instead of just “build another feature.”

If you get the capabilities and types right, but you always act at t0 or t+1, you will still lose to those who act at t–2.

That’s the quiet message behind this whole chapter:

Innovation is not just what you do or how you do it.

It’s also when you dare to do it.

Closing - Innovation Part 2

If Part 1 (WHY) was about the logic of innovation,

Part 2 (WHAT) is about the machinery.

It’s not a department.

It’s not an idea.

It’s not a workshop.

It’s a system made of:

the ability to learn faster than the world changes (absorptive capacity),

the courage and structure to reconfigure when it matters (dynamic capabilities),

the sensitivity to weak signals that show up long before consensus,

and the craft to combine product, process, organizational, and business model innovation into something competitors can’t easily copy.

And all of this is only useful if you move at the right moment — early enough to matter, not just late enough to survive.

That’s what separates the hyperscalers from the systems that spend 12 years repairing the past.

Founders face the same choice, just at a smaller scale:

🥤 behave like a hyperscaler - learn, sense, move, reconfigure, and accept risk,

🍺 or behave like a ministry - wait for certainty, outsource risk, and pay the price later.

In the end, innovation is not the pitch deck, not the launch, not the press release.

It’s the set of capabilities that quietly shape your decisions every week.

Next in this series, we’ll go deeper into the hardest part of all:

Disruption - why it happens, why most incumbents miss it, and what bold bets really require from founders and investors.

Stay tuned.

🎚️🎚️🎚️🎚️ Producer’s Note

Nina Hagen Band - “Ich glotz TV”

One of the best German bands ever; live back in 1978 when Germany was thriving. If you are not in punk, … the song gets better and better. Apart form that, she’s a show-off a talent of a different kind. For all not German spoken readers .. don’t worry, we don’t understand all of it either. It’s Punk.

Next week Disruptive Innovation.

Fab 🎱 & Andy 🎓

https://www.ft.com/content/86bb929f-e0ec-4e50-b429-e9259c3834e2

Microsoft — $50B annual capex (AI + datacenters)

CNBC (stable):

https://www.cnbc.com/2024/01/30/microsoft-ai-investments-drive-record-capital-expenditures.htmlAmazon (AWS) — $55B annual infrastructure spend

Financial Times (stable):

https://www.ft.com/content/2045b02d-6524-4a58-8b84-01d2da52d99fGoogle — $30–35B annual capex

Reuters (stable):

https://www.reuters.com/technology/google-boosts-capex-ai-data-centers-2024-04-25/Meta — ~$35B capex for AI and datacenters

Meta Investor Relations (stable):

https://investor.fb.com/investor-news/press-release-details/2024/Meta-Reports-Fourth-Quarter-and-Full-Year-2023-Results/default.aspx

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strategic_early_warning_system

https://josephmahoney.web.illinois.edu/BA545_Fall%202022/Cohen%20and%20Levinthal%20(1990).pdf

https://www.davidjteece.com/dynamic-capabilities

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback