AI 2026: Where AI Actually Creates Value

Notes from the application layer: The economics of AI - why the numbers don’t add up the way most people think

Something strange is happening with AI1.

After the holiday break, one of my children went back to school.

A teacher told the class that a personal decision had been made: not only gaming and AI would be banned during school hours - but the iPad as well. Back to paper. 100%.

Another teacher is planning to join.

Across companies, schools, and institutions, AI is triggering responses that range from fascination to fear - often at the same time. Some lean in. Others pull the emergency brake.

That tension is understandable.

But it also explains why the public debate keeps circling around the same questions.

Is AI a bubble?

Is it a breakthrough?

Is it taking over?

Depending on who you ask, you’ll hear all three - often with equal conviction.

What’s interesting is not that people disagree.

It’s where they are looking when they do.

Because AI doesn’t create impact uniformly. In some places, it barely moves the needle. In others, it seems to change everything at once.

That asymmetry is the key.

1. Asking the Right Questions

For the last two years, the AI debate has circled around the same tired questions.

Is AI a bubble?

Is investing too circular?

Are models commoditizing too fast?

These questions sound reasonable. They are also largely irrelevant.

They frame AI as a belief system - something that might work out, or might not.

That framing no longer matches reality.

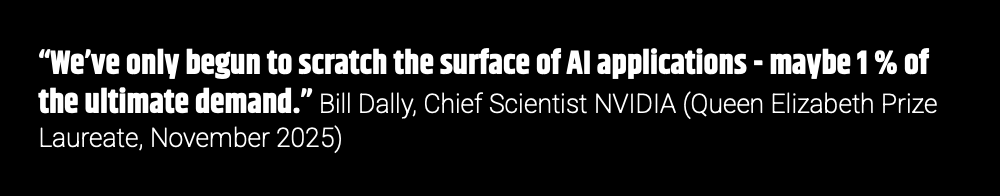

By 2026, AI is not a speculative technology looking for a use case. It is a system already reshaping how work gets done - unevenly, imperfectly, but measurably.

The real question is not whether AI is impressive.

The real question is: Where does AI actually create economic value?

Once you ask that question, the debate changes.

Because AI does not become a world-changing supercycle by producing better answers, nicer demos, or smarter chatbots. It becomes a supercycle only if it changes cost structures, replaces work, and shows up in operating results.

And that is no longer a future promise.

It is already visible - just not where most people are looking.

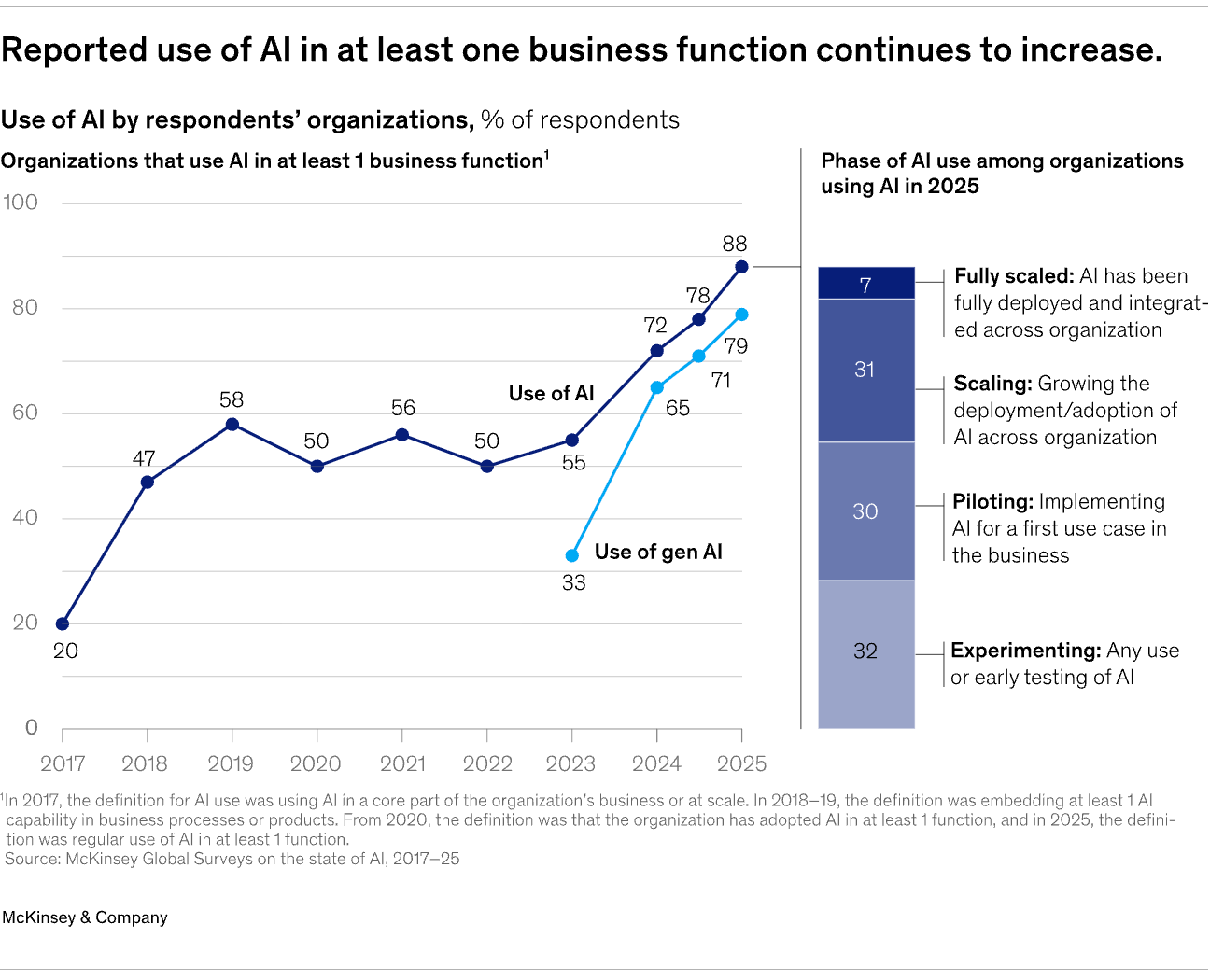

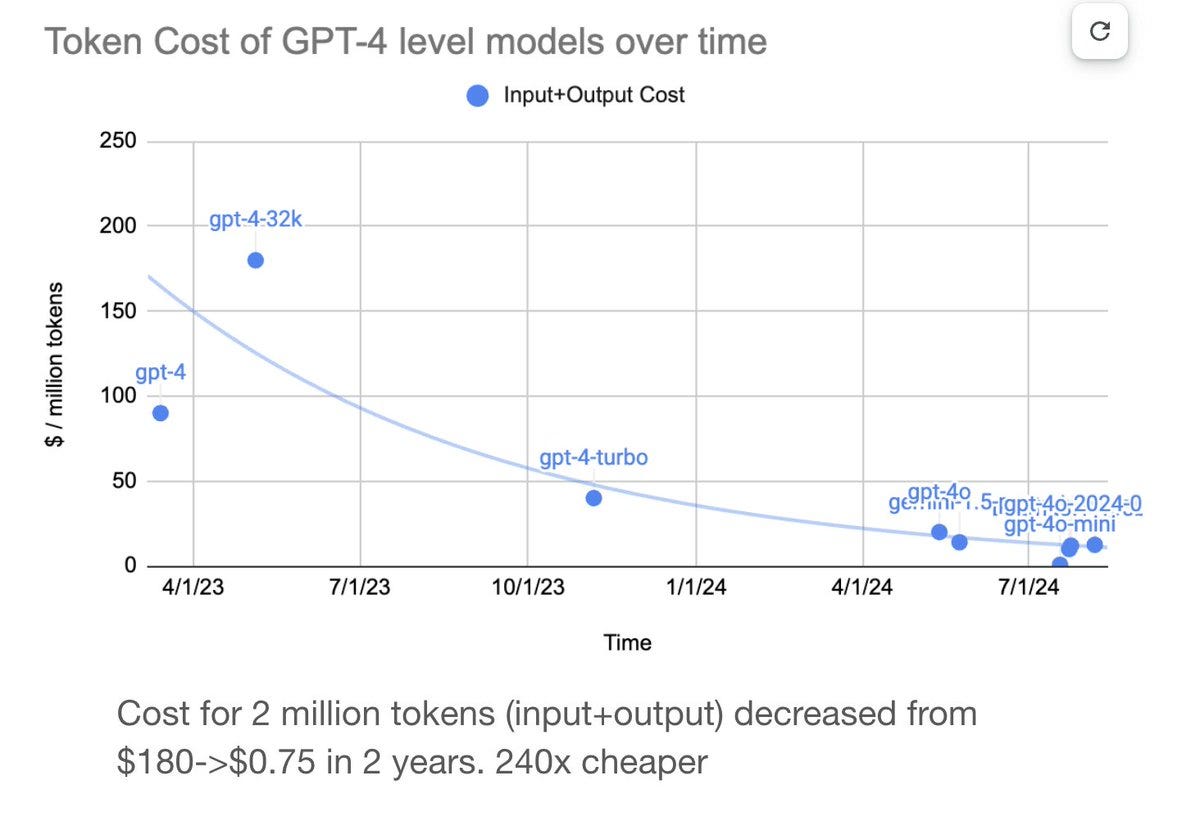

What makes this moment different is not that the technology suddenly got smarter. It’s that the economics snapped into place. Costs dropped fast enough, reliability improved far enough, and infrastructure scaled wide enough that AI moved out of experimentation and into production.2

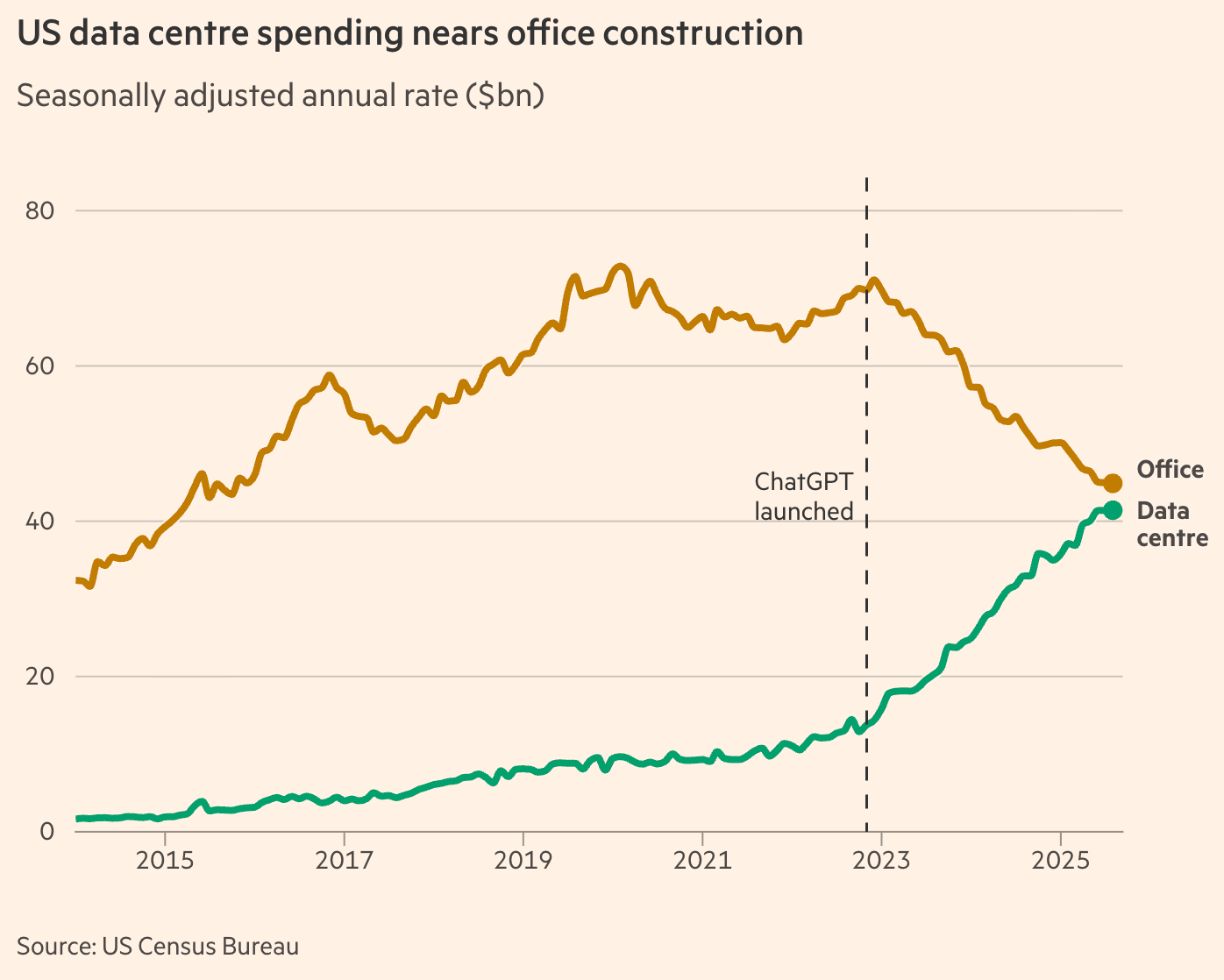

At the same time, the companies investing the most are not guessing. They sit at the center of global computation. They see usage patterns, workload shifts, and internal adoption long before those trends become visible to the market. When they spend hundreds of billions, they are not betting on an abstract future. They are responding to demand patterns they can already observe.

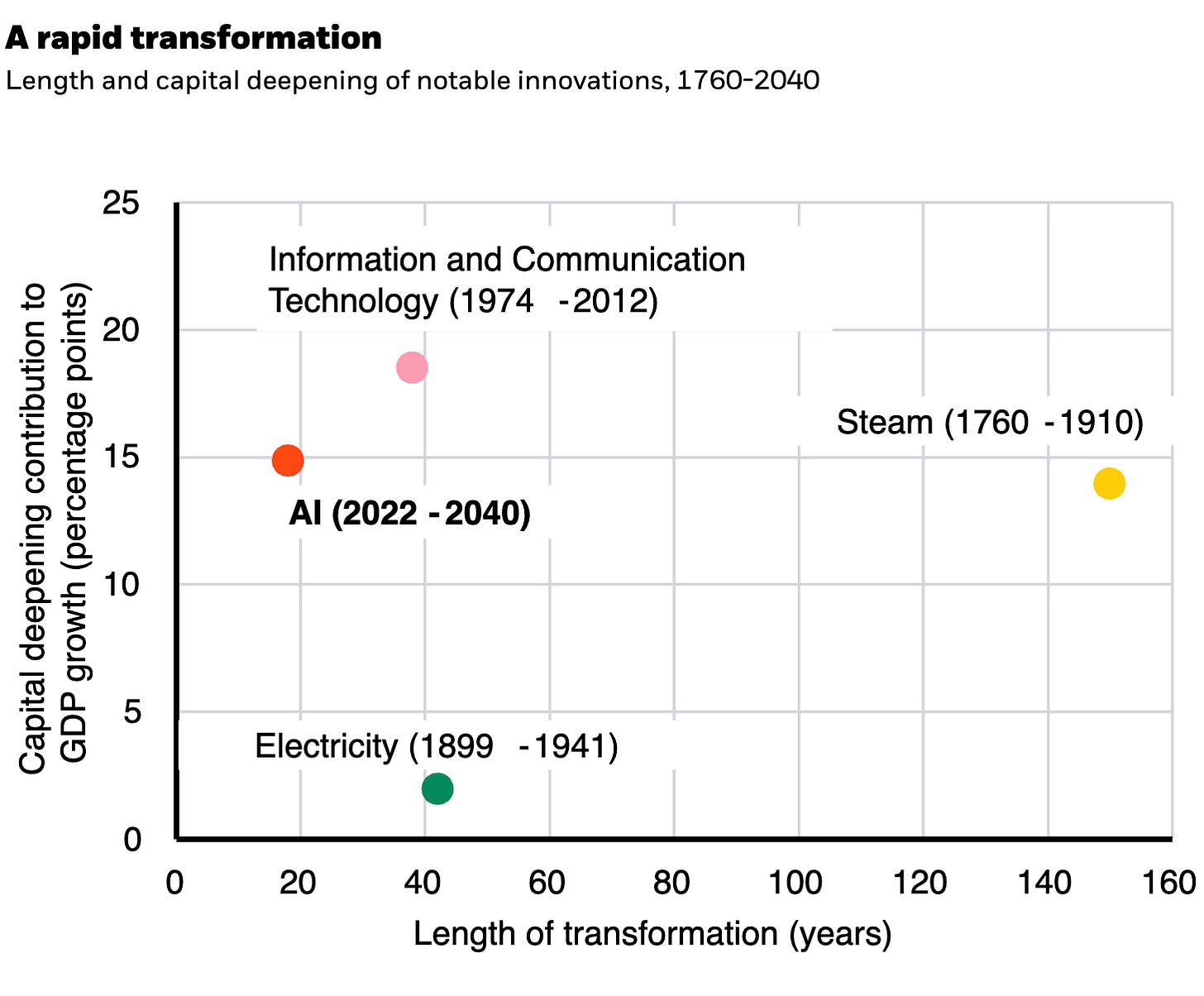

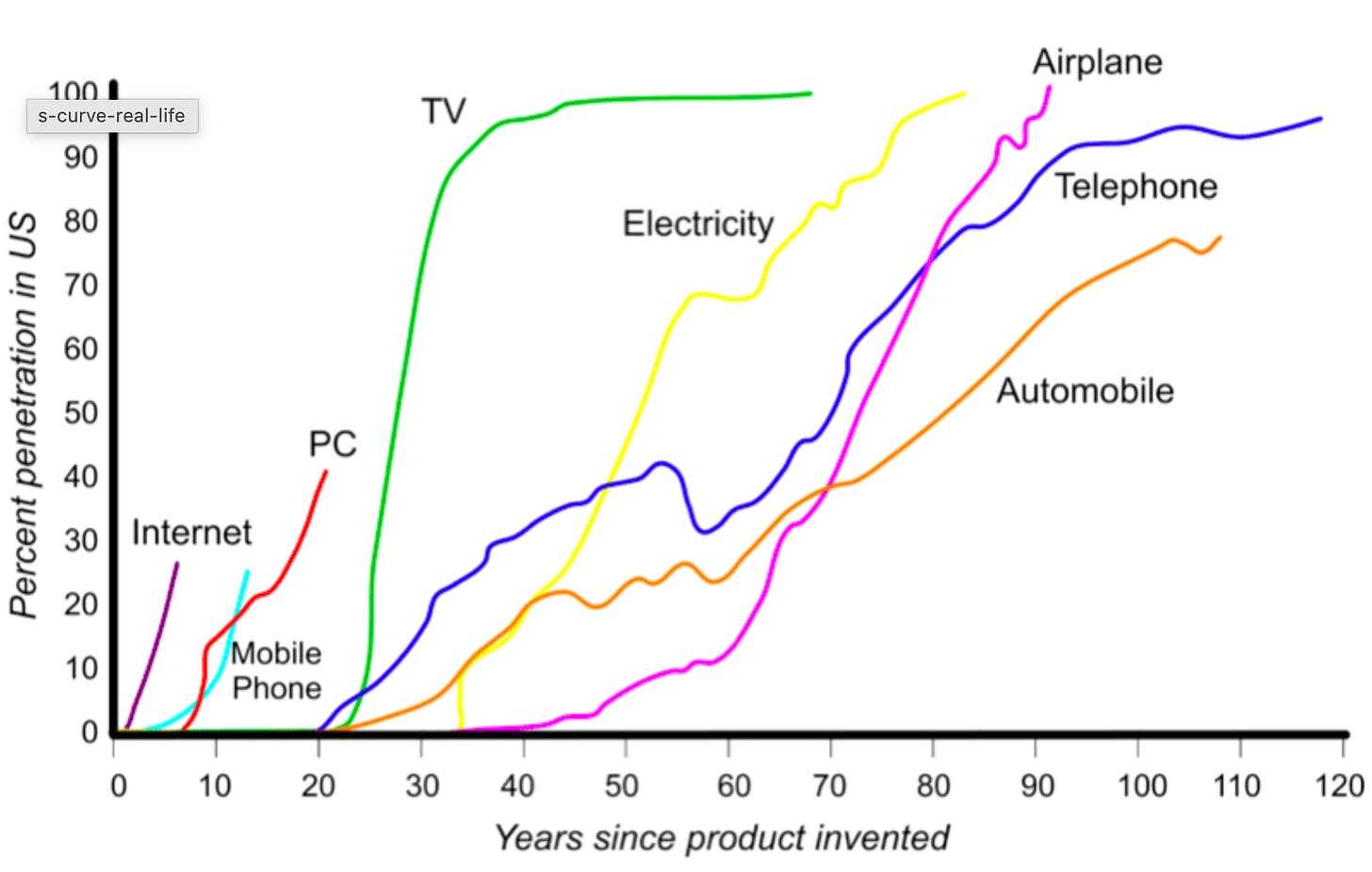

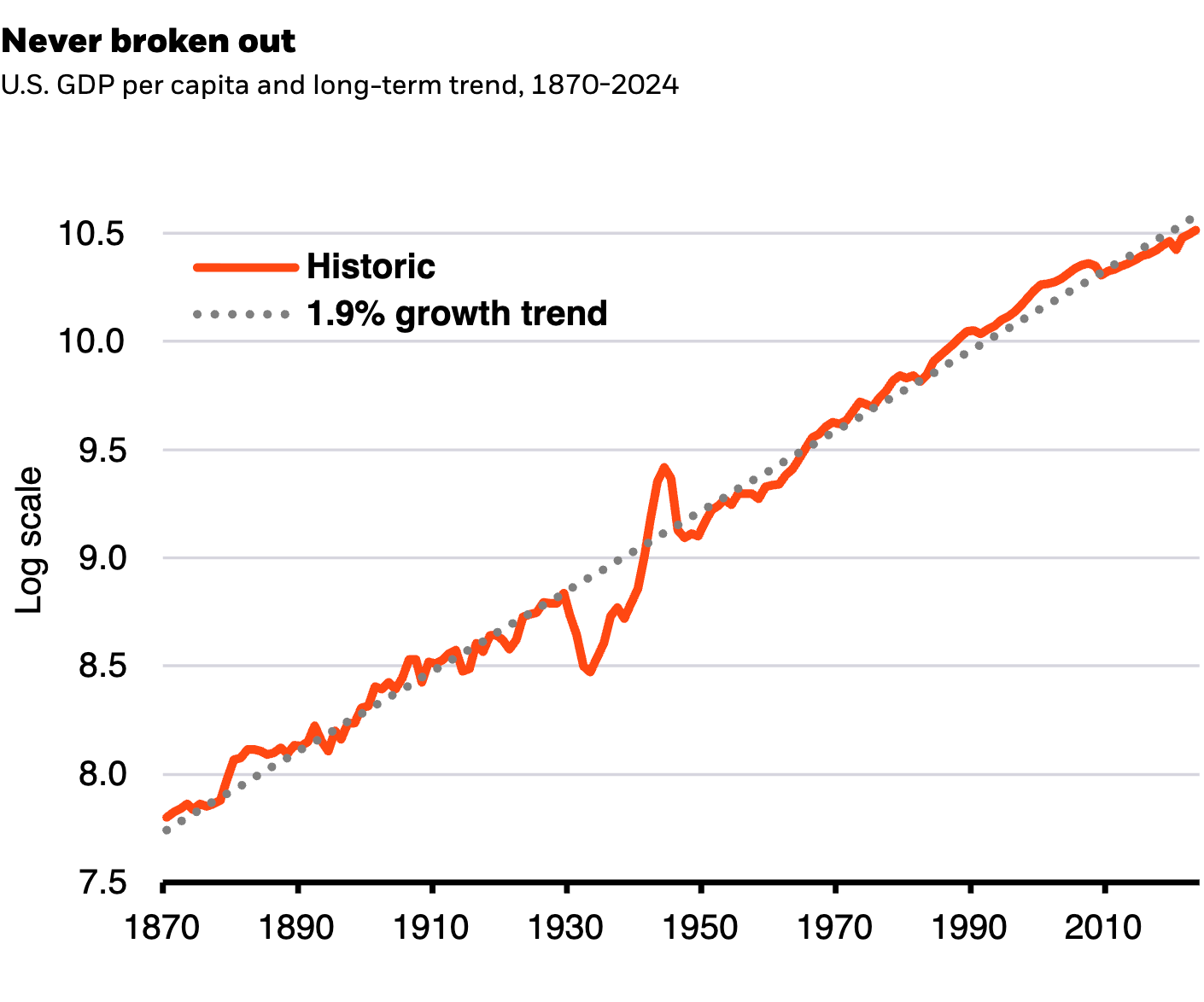

Read together with the chart above, this puts AI into a different historical category. Unlike steam or electricity, the capital deepening is happening faster, at greater intensity, and over a much shorter window. That combination is rare - and it is exactly what defines a genuine economic supercycle (aka: Kondratieff).3

That’s why the question of “bubble or not” misses the point.The more useful question - the one that actually explains what happens next - is this:

Which part of the AI stack turns intelligence into real work?

Answer that, and the rest of the AI story becomes much easier to understand.

2. The Charts - Read It Correctly

Let’s start with a chart :)

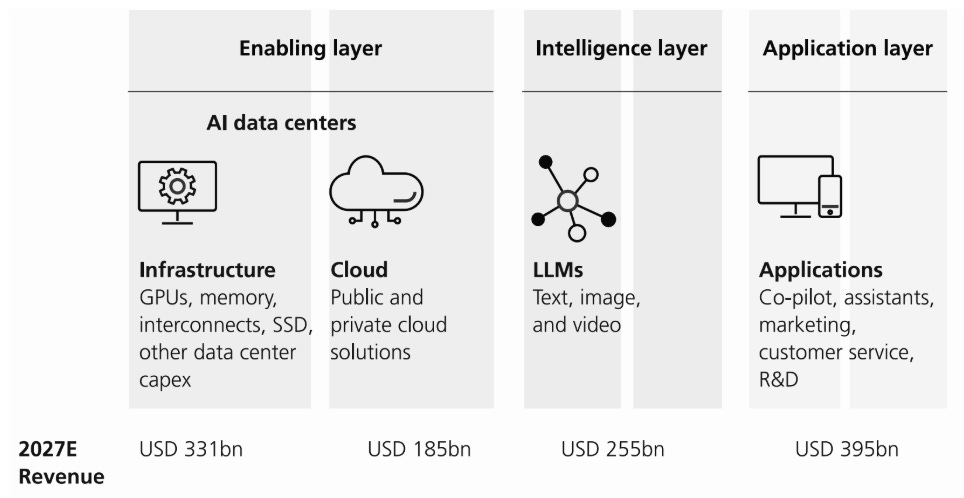

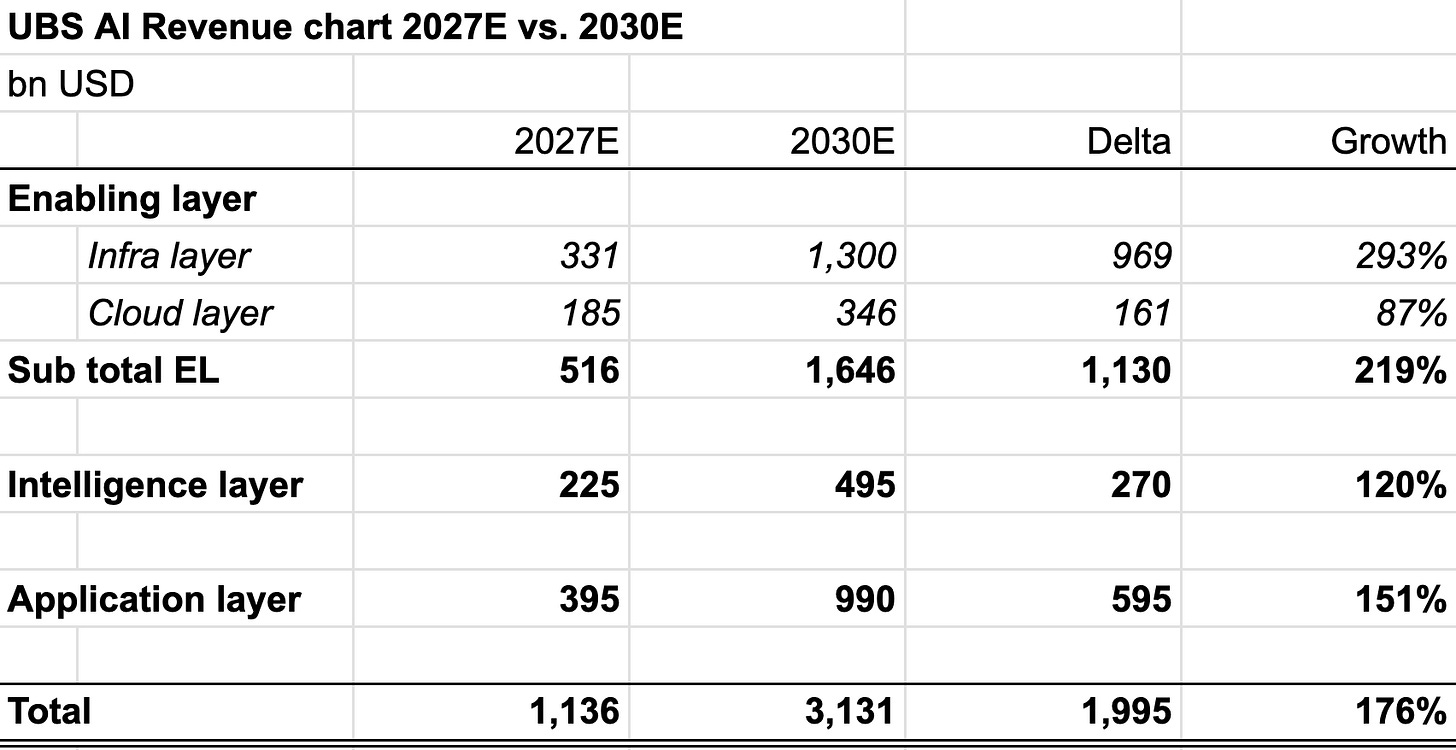

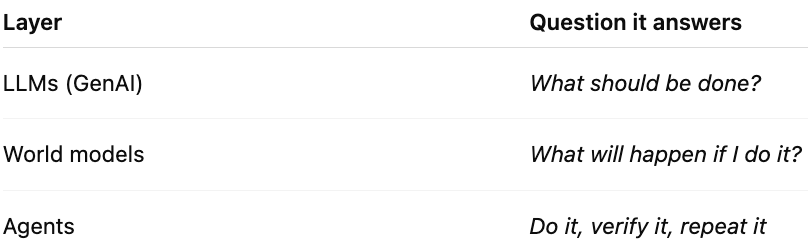

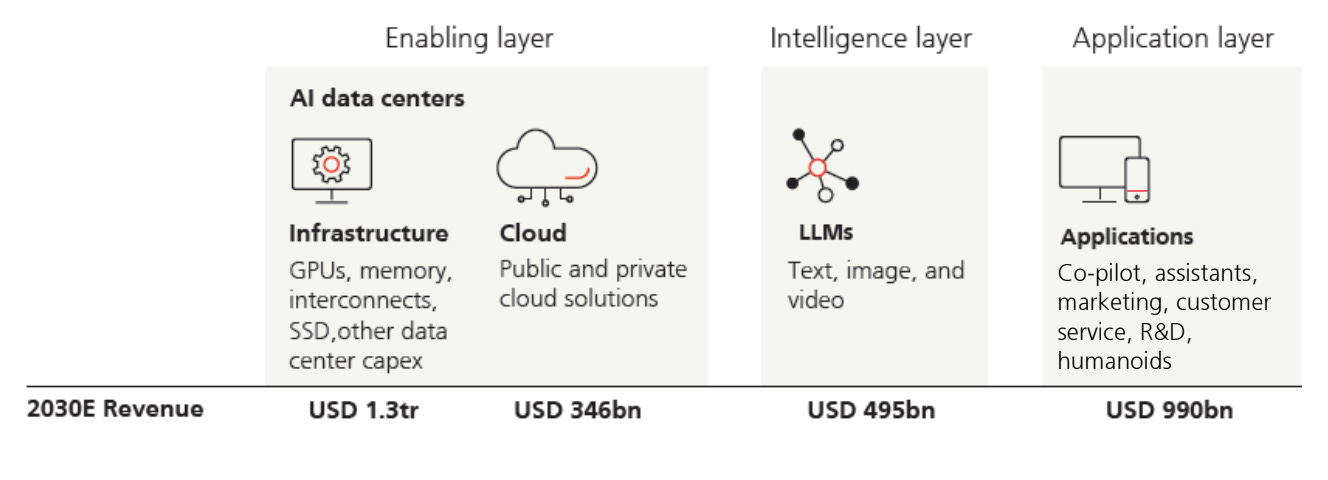

UBS recently published a chart that splits AI into three layers:4

The enabling layer

Power, chips, data centers, GPUs, networks.The intelligence layer

Large language models: text, image, video, reasoning.The application layer

Copilots, agents, workflows, software that people actually use.

As a comparison: UBS published the same chart a year ago:

The growth from 2027E to 2030E is impressive:

On paper, all three look important.

In reality, they are not equal.

Not a chart.

Not data.

Just interpretation.

Here is the uncomfortable truth:

If you remove the application layer, AI stops being a supercycle.

You are left with infrastructure and models - impressive, expensive, and limited in impact.

AI without applications is like a Formula 1 car without tires.

Amazing engineering. Loud. Mostly useless.

This is where many discussions go wrong. Infrastructure and intelligence are often treated as the main story. They are not. They are prerequisites.

A more accurate way to read the stack is this:

Infrastructure enables

Intelligence equalizes

Applications capture value

Infrastructure makes AI possible, but it absorbs enormous capital and only pays off if it is used productively. Intelligence spreads quickly, improves fast, and becomes cheaper over time. On its own, it raises capability but rarely reshapes cost structures.

Only the application layer converts AI into something that shows up in GDP, margins, and operating results.

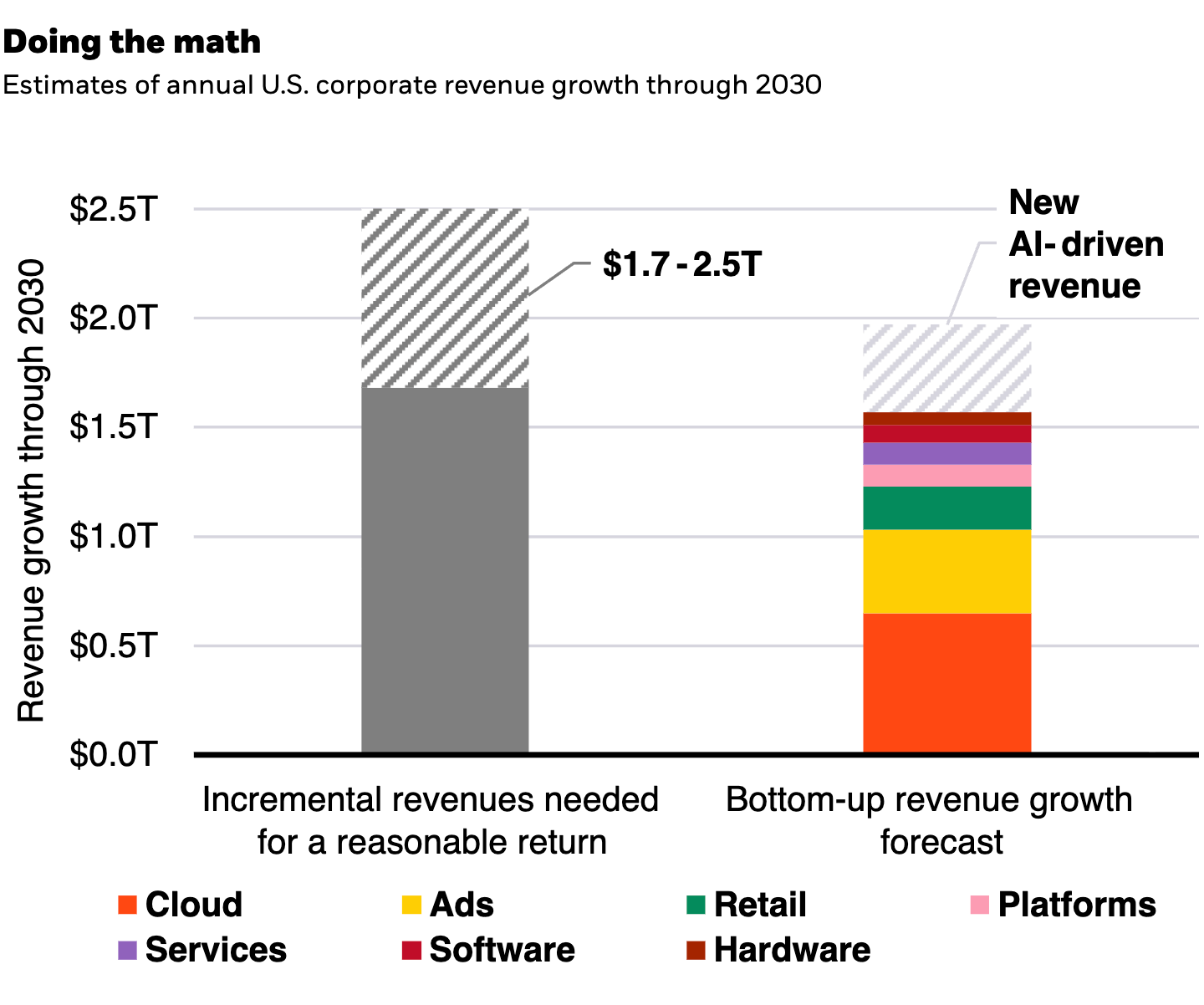

UBS forecasts USD 3.1 trillion in AI revenue by 2030, implying a roughly 30% six-year CAGR across the enabling, intelligence, and application layers.5

You can see this clearly if you mentally remove each layer:

Remove infrastructure, and nothing works.

Remove intelligence, and applications stall.

Remove applications, and the entire system loses its economic justification.

This is why the application layer is not “one of three.”

It is the layer that determines whether AI becomes a lasting economic transformation, or just an impressive technological phase.

The charts show that the application layer must matter.

They do not explain why.

To understand where value actually accrues - and why AI behaves so differently across layers - we need to look at how the stack works economically in the real world.

3. How the AI Stack Actually Works (and Where Value Accrues)

Before arguing about bubbles, valuations, or who is “winning” in AI, it’s worth getting one thing straight: how the system actually behaves in the real world.

Not in marketing language.

Not in benchmark scores.

But in economic reality.

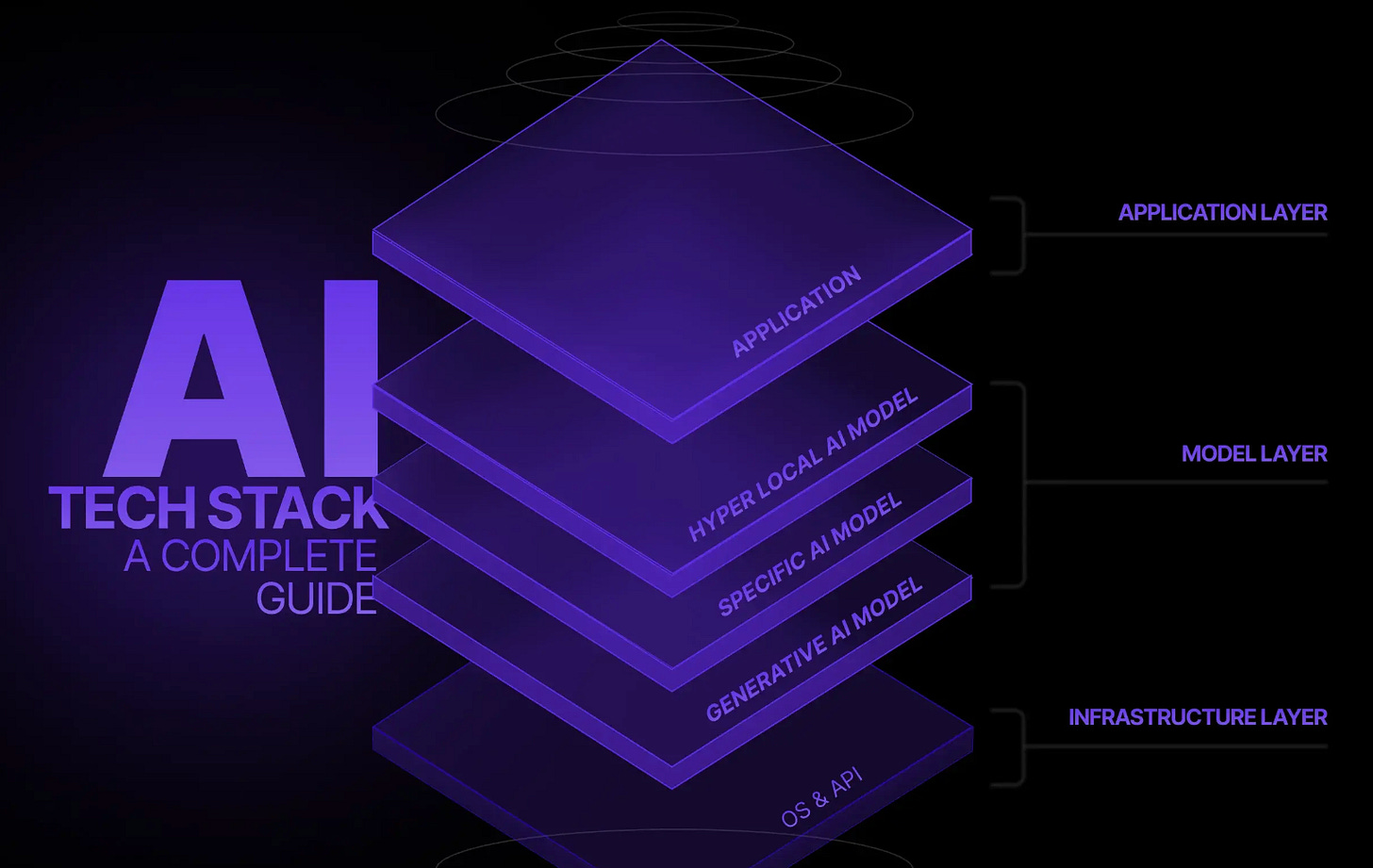

AI today operates as a stack with three layers:

– infrastructure

– intelligence

– applications

All three are necessary.

But they do not behave the same way economically — and they do not create value in the same place.

Understanding that difference is the key to understanding why AI is becoming inevitable in some areas, commoditized in others, and transformative only in one.

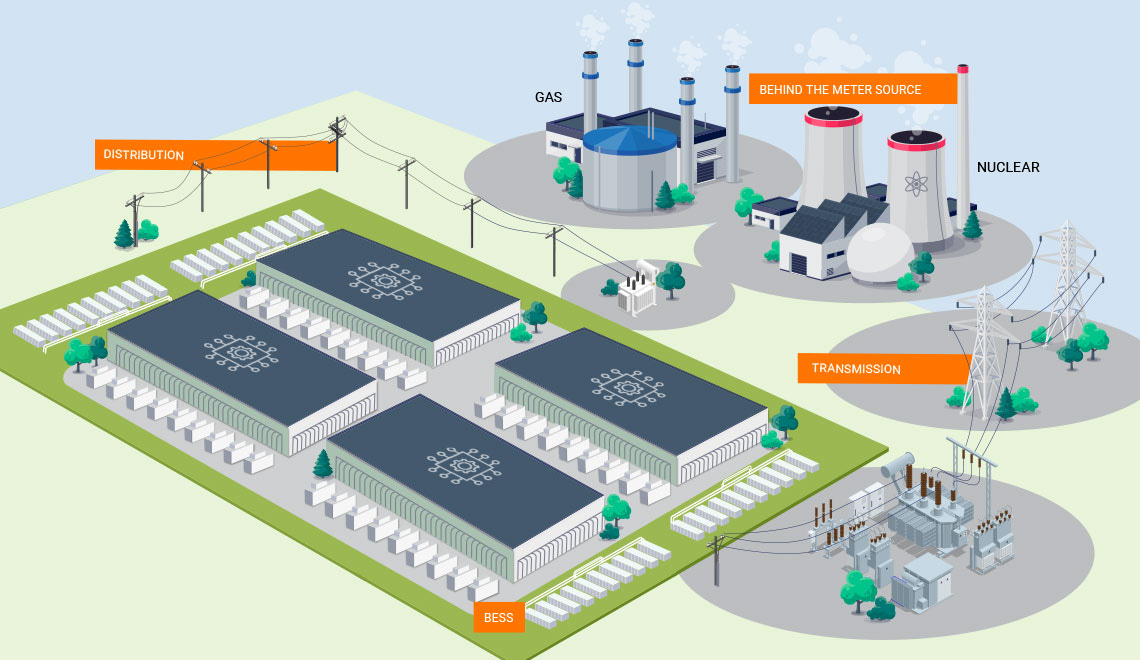

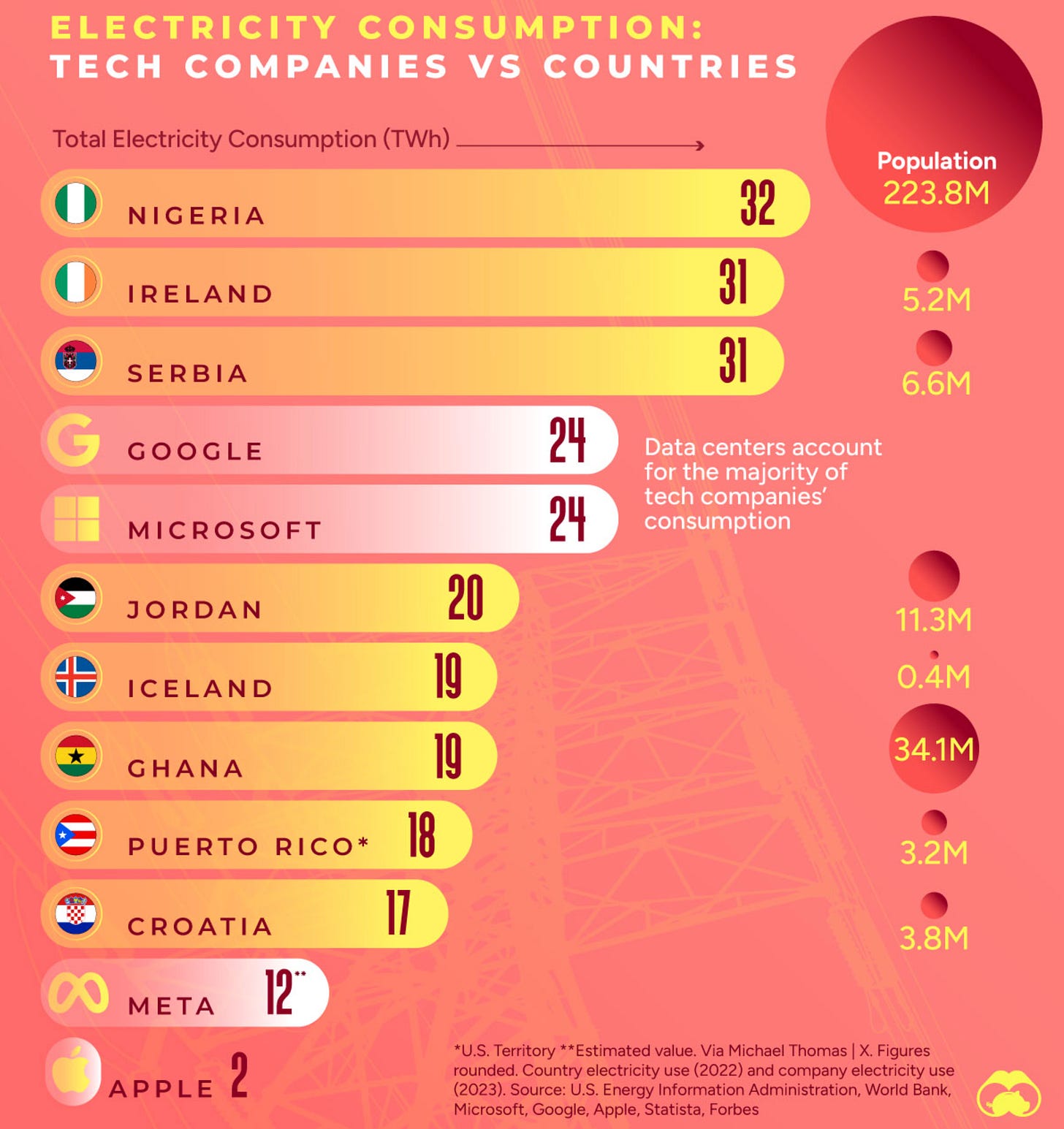

3.1 The Infrastructure Layer: Power, Chips, and Strategic Certainty

This is where the AI story quietly became much bigger than most people realize.

On the surface, the infrastructure layer looks familiar: GPUs, data centers, cooling, power, capital expenditure numbers that keep getting larger. We’ve seen infrastructure cycles before: cloud, mobile, broadband.

But what’s happening now is different in one crucial way.

The shift from NVIDIA’s Hopper generation to Blackwell is not a normal chip upgrade. It marks the moment where AI scaling stops being a software problem and fully collides with the physical world. Blackwell systems are designed for extreme-scale AI workloads, delivering dense compute and novel cooling approaches purpose-built for generative AI inference and training.6

Previous generations were incremental. You could slot them into existing data centers with air cooling and familiar power assumptions.

Blackwell breaks that pattern.

Suddenly:

air cooling is no longer sufficient

liquid cooling becomes mandatory

power density explodes

rack weight increases so much that buildings themselves become a constraint

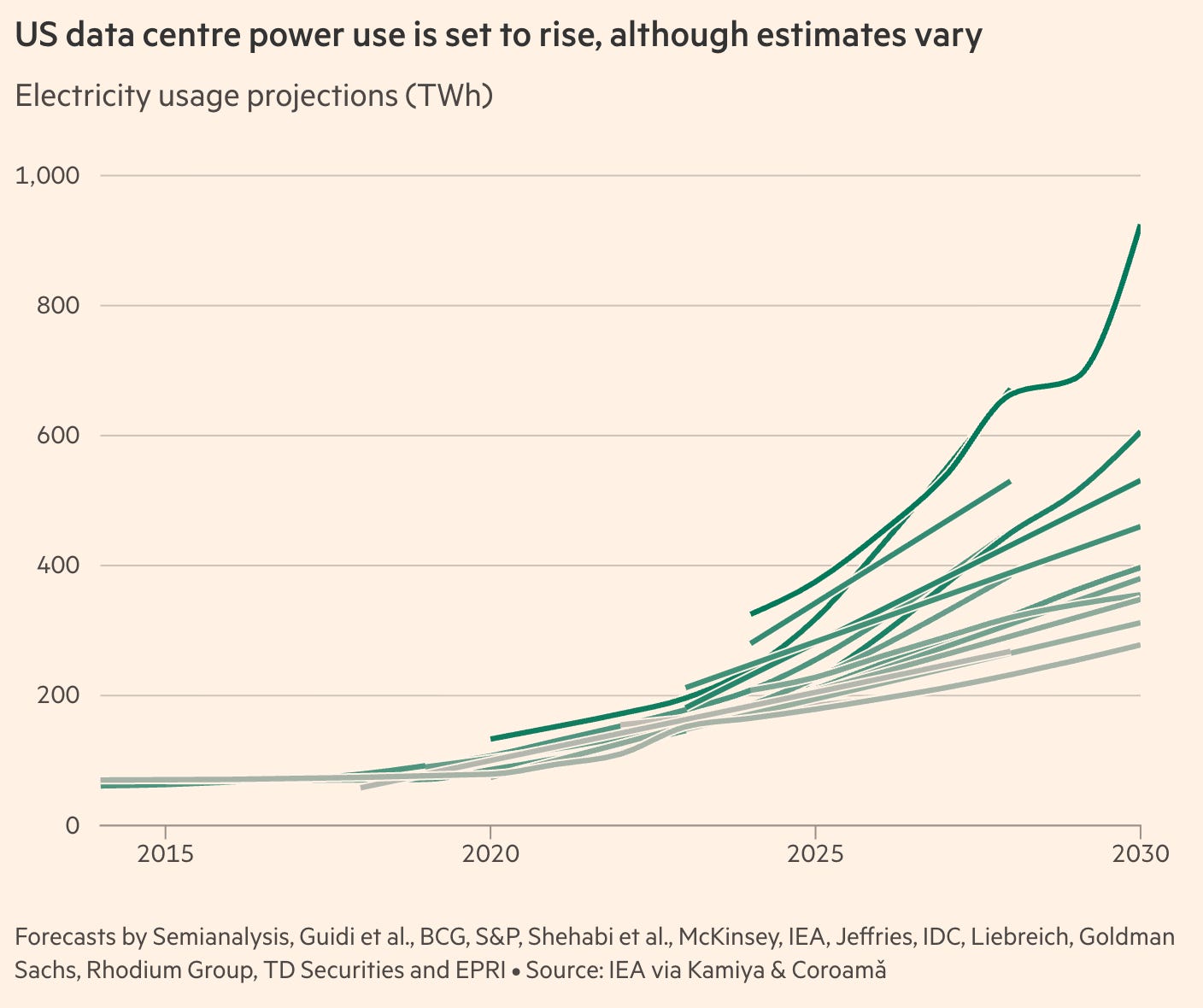

These high-density demands are precisely why operators are expanding liquid cooling and hybrid systems in data centers - a trend driven by AI workloads that push rack power beyond what traditional air cooling can handle.7

This is not a performance upgrade.

It’s a structural upgrade.

That’s also why the rollout was not smooth. The delays weren’t about poor execution or overpromising. They were about reality. You can design a chip faster than you can redesign data centers, reinforce floors, reengineer cooling systems, and bring new power capacity online.

Getting massive, reliable power delivered - often years in planning - is now a gating factor for new AI sites.8

And this is just the beginning.

The next generation after Blackwell (e.g. NVIDIA Rubin) is expected to push even further in the same direction: higher density, more aggressive cooling assumptions, and deeper integration of memory and networking within racks. Once you cross this threshold, there is no going back. AI infrastructure now behaves more like heavy industry than traditional software stack scaling - a point analysts have highlighted as power and siting become central strategic considerations.9

This has profound strategic consequences.

Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and a small handful of others are no longer just buyers of compute. They are redesigning the physical foundations of how computation exists:

securing long-term power contracts and even buying generation assets outright

reshaping real-estate strategy for massive campus footprints

rethinking data center architecture from the ground up

Major tech groups are even acquiring energy infrastructure providers to accelerate reliable supply for AI sites, recognizing that electricity availability is now a core determinant of growth.10

From the outside, this can look like a massive bet.

From the inside, it doesn’t.

These companies sit at the center of global computation. They see real usage across millions of services and billions of users. They see how workloads shift, which teams adopt agents, where tokens get cheaper, and where friction disappears. They don’t rely on forecasts alone - they watch behavior change in real time, inside their own systems.

That’s why this infrastructure build-out has a self-reinforcing quality.

💻 More compute lowers costs.

🔓 Lower costs unlock new applications.

🚀 New applications drive more usage.

🔁 More usage justifies more infrastructure.

This loop doesn’t require belief. It runs on data.

At the same time, the broader energy context matters. By 2028, a significant amount of additional power capacity is expected to be needed just to meet AI facility demands, further underscoring how electricity supply has become a strategic constraint in the industry.11

Power, not intelligence, has become the binding constraint. That’s why concepts like “Time-to-Power” now matter more than Moore’s Law. If you can’t deliver electricity fast enough, your models don’t matter.

This also puts strategies like Google’s TPUs into proper context.

Vertical integration makes sense. TPUs and custom ASICs optimize internal workloads and cost control. But they don’t escape the same physical realities: power density, cooling, buildings, and capital still dominate. The constraint is not who designs the chip - it’s who can deploy it at scale in the real world.12

This is why infrastructure alone can never be the winner.

It enables everything above it.

It absorbs enormous capital.

And it only pays off if it is used for productive, revenue-generating work.

That’s the bridge to the next layer - and where the real economic story begins.

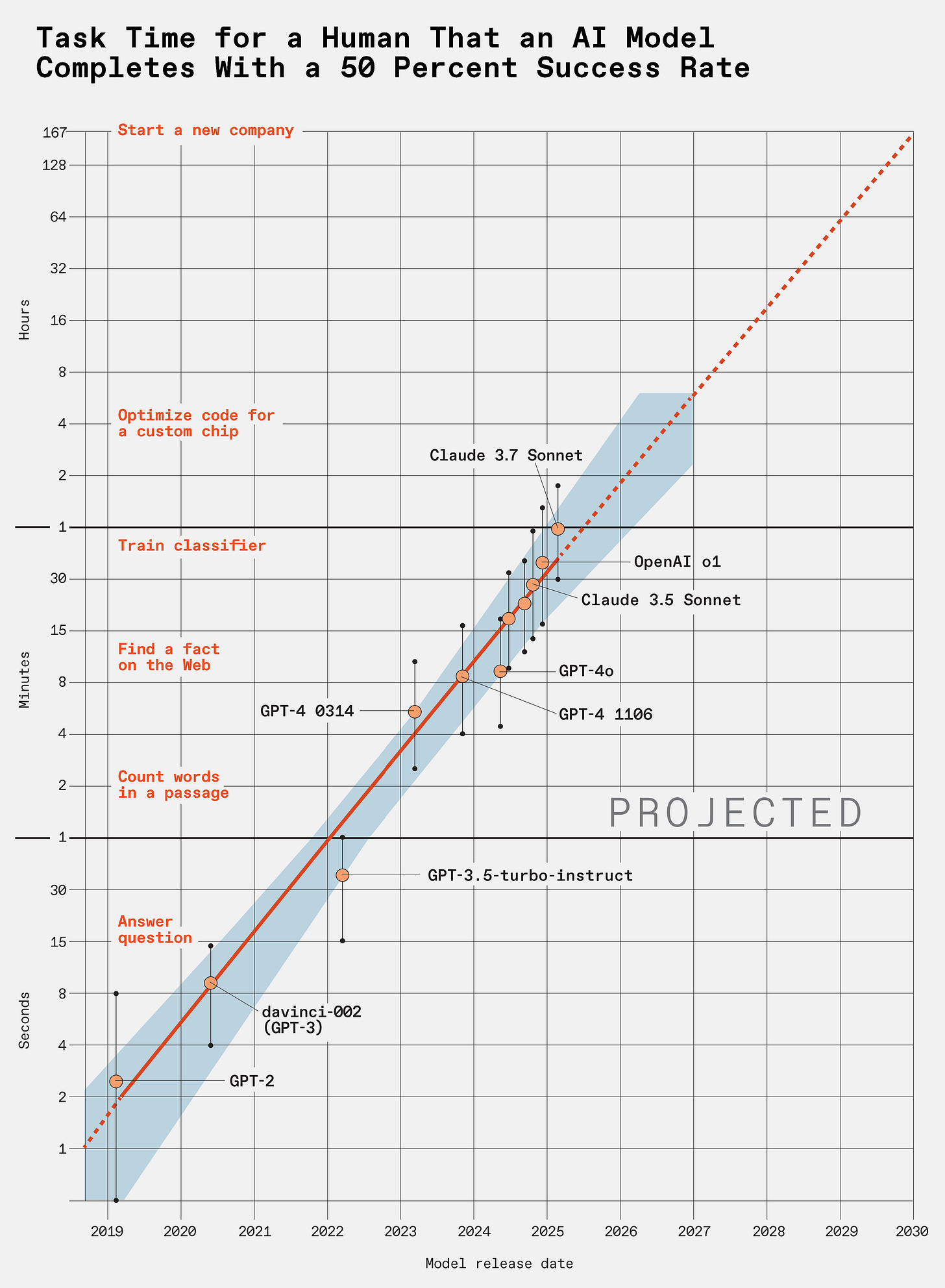

3.2 The Intelligence Layer: Why Models Improve Fast - and Value Doesn’t

If infrastructure is where AI collides with the physical world, the intelligence layer is where many people get misled.

This is where most headlines live.

New models.

Better benchmarks.

Bigger context windows.

Stronger reasoning.

And all of that is real.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Improvements at the model layer do not automatically translate into economic value.

In fact, the opposite is often true.

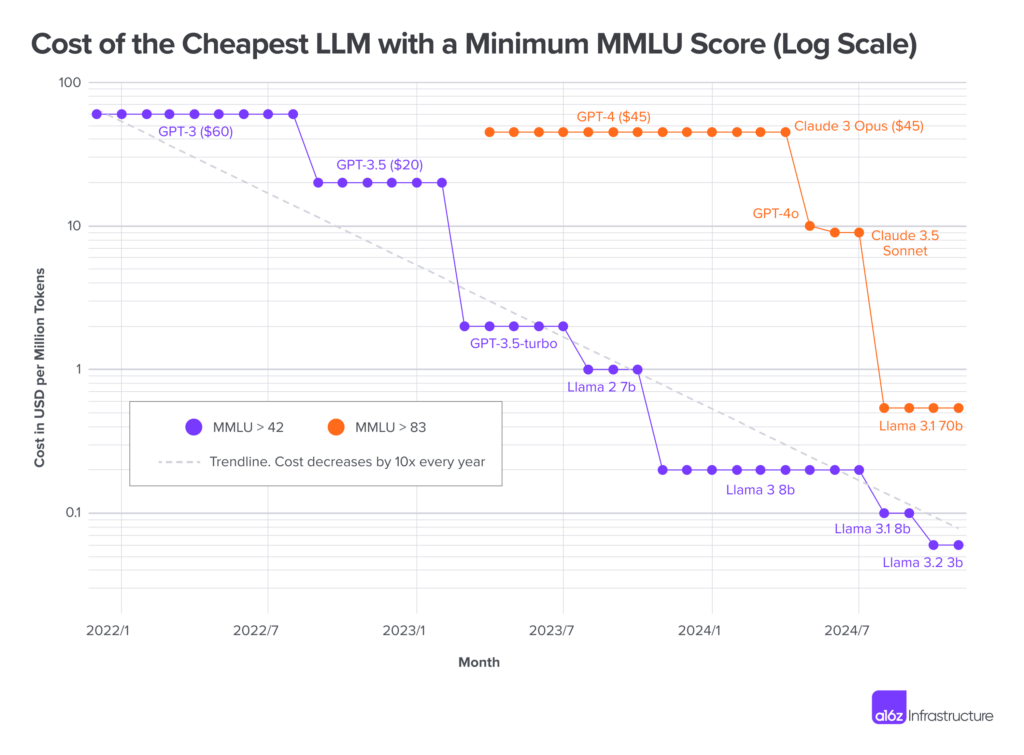

The intelligence layer is improving so fast precisely because it is becoming cheaper, more standardized, and easier to replicate. That’s not a weakness of AI — it’s a sign of maturity. But it changes where value can accrue.13

We’ve seen this pattern before.

Wikipedia made knowledge universally accessible.

Google Search made information instant.

Both were revolutionary.

Neither, on their own, replaced large parts of the workforce or reshaped corporate cost structures.14

Large language models sit much closer to those examples than many people want to admit.

They are exceptionally good at producing answers, summaries, drafts, and suggestions.

They dramatically raise the baseline of what an individual can do.

But raising the baseline is not the same as creating operating leverage.

Execution creates leverage.

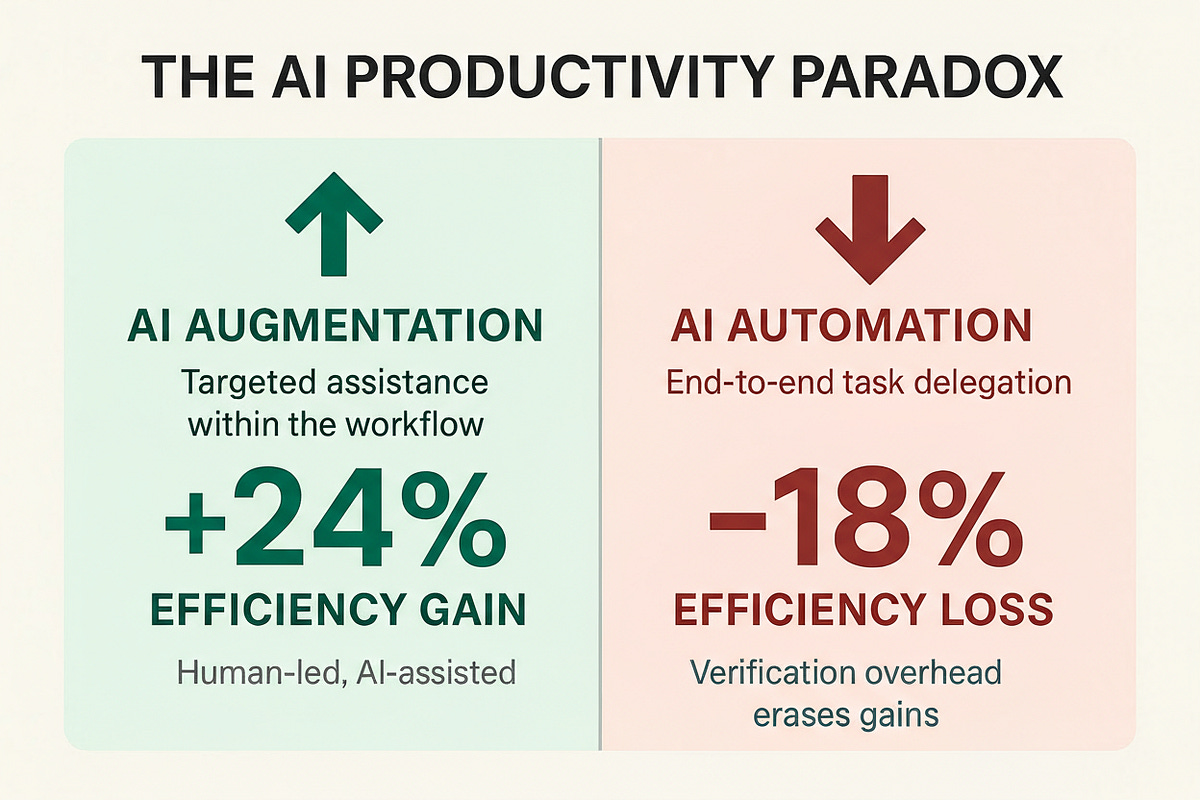

This is where - again - Gavin Baker’s framing is particularly useful.

In most past technology cycles - phones, SaaS, social media — being the lowest-cost producer didn’t really matter. Apple was never the cheapest phone. Microsoft was never the cheapest software vendor. Value came from distribution, ecosystem, and lock-in.

AI breaks that pattern.

Every AI output has a marginal cost.

Every response burns compute.

Every improvement in reasoning increases token usage.15

For the first time in decades, unit economics matter again.

This is why cost-per-token has become a strategic variable, not just an engineering metric. And it’s why the intelligence layer is converging faster than many expected.16

When models get cheaper:

experimentation explodes

switching costs drop

differentiation erodes

That’s great for adoption.

It’s terrible for sustained value capture at the model layer.

This also explains why the gap between “frontier” and “good enough” models matters less economically than it appears technically.

For many real-world tasks, the difference between the best model and the second-best model simply isn’t decisive - especially once price, latency, and reliability enter the equation.17

This is where strategies like Google’s come into focus.

Google’s investment in TPUs and vertical integration is rational. It allows them to control internal costs and optimize their own workloads. But it also highlights a deeper point:

The strategic game has shifted from intelligence to efficiency.18

The question is no longer: Who has the smartest model?

It’s: Who can deliver intelligence cheaply, reliably, and at scale - without blowing up their cost structure?

And once intelligence becomes abundant and affordable, its standalone value collapses.

This doesn’t mean models stop mattering.

They matter enormously.

But they matter as inputs, not as the place where economic value concentrates.

The intelligence layer enables everything above it.

It lowers barriers.

It accelerates experimentation.

But by itself, it mostly creates capability - not returns.

That distinction is critical.

Because it explains why the AI story only becomes economically decisive in the layer above: The Application Layer.

3.3 The Application Layer: Why the Breakout Starts Here

This is also the layer where we’ve been spending most of our time at StudioAlpha.

Over the last two years, we’ve invested in and worked hands-on with 15 AI-native startups - all building applications, not infrastructure, not models.

What we’ve seen up close matches the macro picture: the real breakthroughs don’t come from smarter models, but from applications that move into production and start doing work.

If a real productivity breakout happens - the kind BlackRock now calls conceivable - it will not start with more data centers or better benchmarks.19

The breakout will start with applications.

It’s a constraint of how GDP actually grows.

In other words, what BlackRock is pointing at is not a model breakthrough, but a shift in how enterprise software itself is built and used - from tools humans operate to systems that execute work.

Productivity at the macro level only moves when output increases in sectors that matter: healthcare, industry, engineering, logistics, finance. In other words, B2B, not consumer chat. You don’t get a GDP-per-capita breakout because people write nicer emails or cook a good dish. You get it because fewer people are needed to do the same amount of economically relevant work - or because the same people suddenly produce much more.20

That immediately points to the application layer.

But to understand why this moment is different, it helps to look at what enterprise software has been until now - and why it never delivered that kind of step-change.

Why B2B SaaS Never Triggered a Productivity Breakout

For the last 20 years, B2B SaaS followed a remarkably consistent pattern.

Companies like Salesforce, ServiceNow, Atlassian, or SAP built static software systems. You deployed them once - on-premise in the early days, later in the cloud - and then humans did the work inside those systems.

The software:

stored data

enforced workflows

coordinated people

But it didn’t execute work.

Productivity gains were real, but incremental:

better visibility

fewer errors

smoother coordination

Economically, this showed up as:

high gross margins

recurring revenue

steady but capped efficiency gains

Crucially, headcount still scaled with output. You needed more support agents, more sales reps, more analysts as the business grew. Software made people better, but it didn’t replace the work itself.

That’s why, despite decades of digitization, long-term GDP-per-capita growth barely moved. Software improved how work was done - not who or what did it.21

This is the ceiling legacy SaaS never broke through.

What Changes with AI-Native Applications

AI-native applications are built on a completely different assumption.

Instead of shipping a static product and letting humans operate it, they generate behavior on the fly. The software doesn’t just guide a workflow, it executes it.

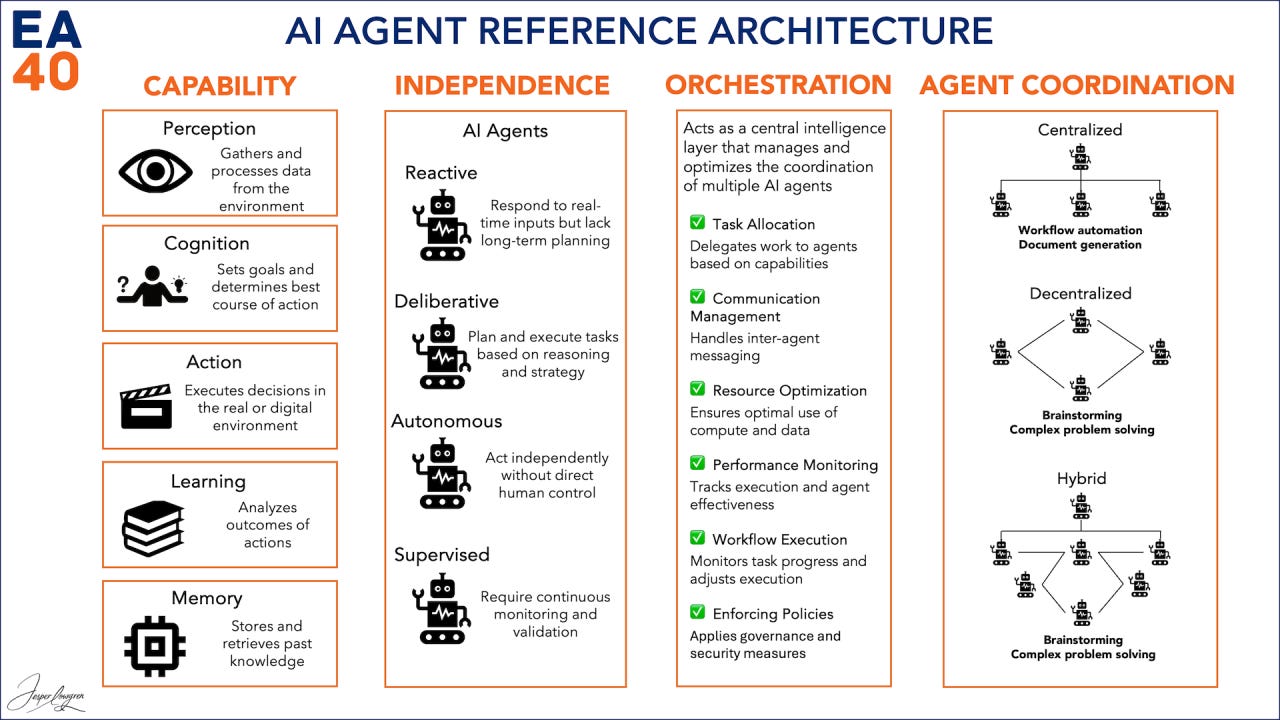

This is where agents enter the picture.

An agent is not a feature.

It’s not a UI improvement.

It’s not a smarter form.

An agent is software that:

takes responsibility for a task

operates across systems

runs continuously

produces a verifiable outcome

This is the fundamental break.

Once software starts doing work instead of supporting it, the economics flip.

Applications → Agents → Labor Replacement → ROI

This is the chain that matters - and why the application layer is the trigger.

Applications embed AI directly into real workflows.

Not as assistance, but as execution.

Those applications are built around agents - systems that can qualify leads, resolve support tickets, reconcile accounts, generate code, run tests, or prepare regulatory filings without constant human supervision.

When agents work reliably, labor is replaced at the task level:

not entire jobs overnight

but enough tasks that headcount growth slows or reverses

That’s when the economics become visible.

Revenue stays flat or grows.

Output increases.

Employee count stagnates or falls.

Return on invested capital improves.

Circling back to Gavin Baker: This is exactly the pattern points to when he says the strongest evidence for AI is not demos, but audited financials. The companies seeing real AI returns are not showcasing the smartest models - they are quietly removing work from their systems.22

And this is also why margins look “worse” at first.

AI-native applications generate everything on the fly. Every action consumes tokens. Gross margins drop compared to classic SaaS. But operating leverage improves dramatically because labor costs fall faster than compute costs rise.

Lower margins.

Higher profits.

We’ve seen this movie before - in e-commerce, in cloud computing, in logistics. The winners accepted margin pressure early to unlock scale and dominance later.

Why This Pulls the Entire Stack Behind It

This is where the BlackRock chart comes back into focus.

Application-level breakthroughs don’t just create value on their own. They pull demand through the rest of the stack.

When agents move into production:

token usage explodes

inference runs continuously

context windows grow

reliability requirements rise

That demand justifies:

more models

more infrastructure

more power

Not the other way around.

Infrastructure doesn’t create the breakout.

Intelligence doesn’t trigger it either.

Applications do.

They are the spark that turns capability into growth - and the reason the AI story finally escapes the lab, the demo, and the pilot phase.

That’s why, if the productivity breakout happens, it will start here.

Seen from this angle, the limits of the intelligence layer become obvious. If applications are what trigger real productivity gains, then better models alone - no matter how impressive — cannot sustain the economic logic of the AI buildout. That is where many narratives still go wrong.

4. Why LLMs Alone Cap the Upside

By now, the pattern should be clear.

Infrastructure scales.

Models improve.

Costs fall.

And yet, none of this alone explains why AI would justify the scale of capital now being deployed - or why it would lead to a genuine productivity breakout.

That’s because large language models, on their own, are not an economic endpoint.

They are an input.

Intelligence Is Not Output

The intelligence layer has delivered something remarkable:

high-quality reasoning at rapidly declining cost.23

But intelligence, by itself, does not create economic output.

It creates capability.

A model can explain a problem, summarize options, draft a solution - but …unless that intelligence is embedded into a system that executes, nothing changes in the real economy.24

This is why comparisons to search engines or encyclopedias are misleading but instructive.

Search transformed access to information.

It did not replace work.25

LLMs do the same - unless they are wired into applications that turn reasoning into action.

That distinction is where the upside either materializes or stalls.

Cost-per-Token Is the New Capital Cost

Once intelligence becomes abundant, the economics shift.

Every AI output has a marginal cost.

Every decision burns tokens.

Every additional step consumes compute.

At scale, token costs behave less like software fees and more like capital costs.

This is new.

Traditional SaaS improved productivity while preserving high gross margins.

AI-native systems trade gross margin for execution.26

At first glance, this looks worse.

Lower gross margins.

Higher variable costs.

Less predictability.

But that view misses the second-order effect. When agents execute work directly, labor stops scaling linearly with output. That’s the real economic break.

Agents Change the Shape of the Firm

Agents are not features.

They are not copilots.

They are not better user interfaces.

Agents are systems that:27

take responsibility for tasks

operate across tools and data

run continuously

produce verifiable outcomes

Once deployed reliably, they change the firm’s cost structure.

Not overnight.

Not by eliminating entire roles.

But by removing enough tasks that headcount growth slows, flattens, or reverses - even as output grows.

This is where return on invested capital improves.

Revenue stays flat or increases.

Labor input stabilizes or falls.

Compute spend rises - but at a lower rate than labor would have.

Lower margins.

Higher profits.

This is exactly the pattern Gavin Baker points to when he says the strongest evidence for AI is not demos, but audited financials.28

The companies seeing real returns are not talking about intelligence. They are quietly removing work from their systems.

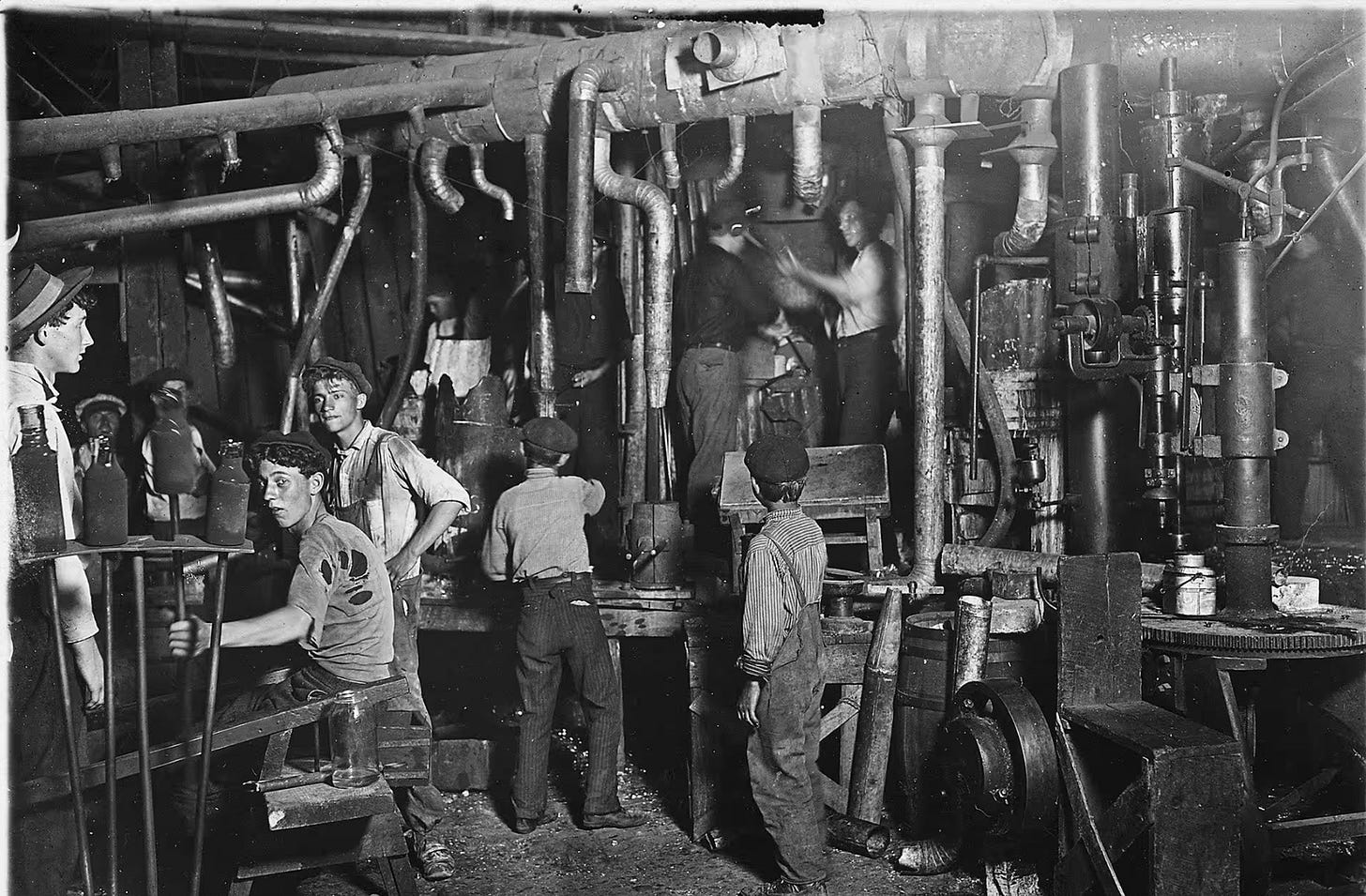

Productivity Shocks Rewrite Labor - History Is Clear

This dynamic is not unprecedented.

Before industrialization, economic output was generated by three factors:

natural resources, labor, and knowledge.

With industrialization, capital entered as a fourth factor - and everything changed.29

Working hours collapsed.

At the same time, GDP per capita exploded.

In Switzerland, for example, real GDP per capita rose from roughly CHF 6,000 in 1920 to over CHF 62,000 by 2012 - while people worked fewer hours than ever before.30

Working hours in Switzerland 🇨🇭:

1830=90h

1870=60h

1924=54h

1964=46h

1971=44h

2020=42h

2036=?

Productivity shocks don’t eliminate value.

They change how it is created.31

AI fits this pattern - with one crucial difference.

For the first time, capital and knowledge can execute work directly.

Agents don’t assist labor.

They absorb tasks.

And token costs - the price of that execution - are the new cost of production.

Why This Closes the Loop

This is why LLMs alone cap the upside.

Intelligence without execution commoditizes.

Infrastructure without applications burns capital.

Only when intelligence is embedded into applications - and applications deploy agents - does AI reshape cost structures in a way that justifies the scale of investment now underway.32

This is also why the supercycle, if it materializes, will not be visible first in benchmarks or product launches.

It will appear quietly.

In firms doing more with fewer people.

In operating margins improving despite lower gross margins.

In compute spend replacing labor spend.

History suggests the economic pie will grow.

What remains unresolved - as it always has - is how that pie gets distributed.33

AI doesn’t answer that question.

But it forces it back onto the table.

And that is usually what marks the end of experimentation - and the beginning of a real economic cycle.

Outro

AI will not change the world because it gets smarter.

It will change the world because it starts doing real work.

Infrastructure makes this possible.

Models make it accessible.

But only applications - agents embedded into workflows - turn intelligence into productivity, ROI, and growth.

If a real productivity breakout happens, it won’t start with another model release or a bigger data center.

It will start quietly, inside companies, where software stops assisting humans and begins executing tasks.

That’s where the AI cycle becomes real.

If this resonates

We spend our time backing and building AI-native application companies - early, hands-on, and with a strong focus on execution over demos.

If you’re a founder working on this layer, or an LP interested in how we approach it, feel free to reach out.

🎚️🎚️🎚️🎚️ Producer’s Note

Early signals. Before the labels. Before the story.

We already had EsDeeKid on our list in the last blog - back then, just as a name among a our 2026 newcomers.

Since then, things escalated a bit. BBC Radio 1 rotation. He is not Chalamet ;]

No big hook.

No overproduction.

Just something that runs.

Have a great start into 2026 ✊🏽

Sources

https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/insights/blackrock-investment-institute/publications/outlook#global-investment-outlook

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/k/kondratieff-wave.asp

https://www.ubs.com/global/en/media/display-page-ndp/en-20251120-year-ahead-2026.html

https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealthmanagement/insights/year-ahead-registration.html

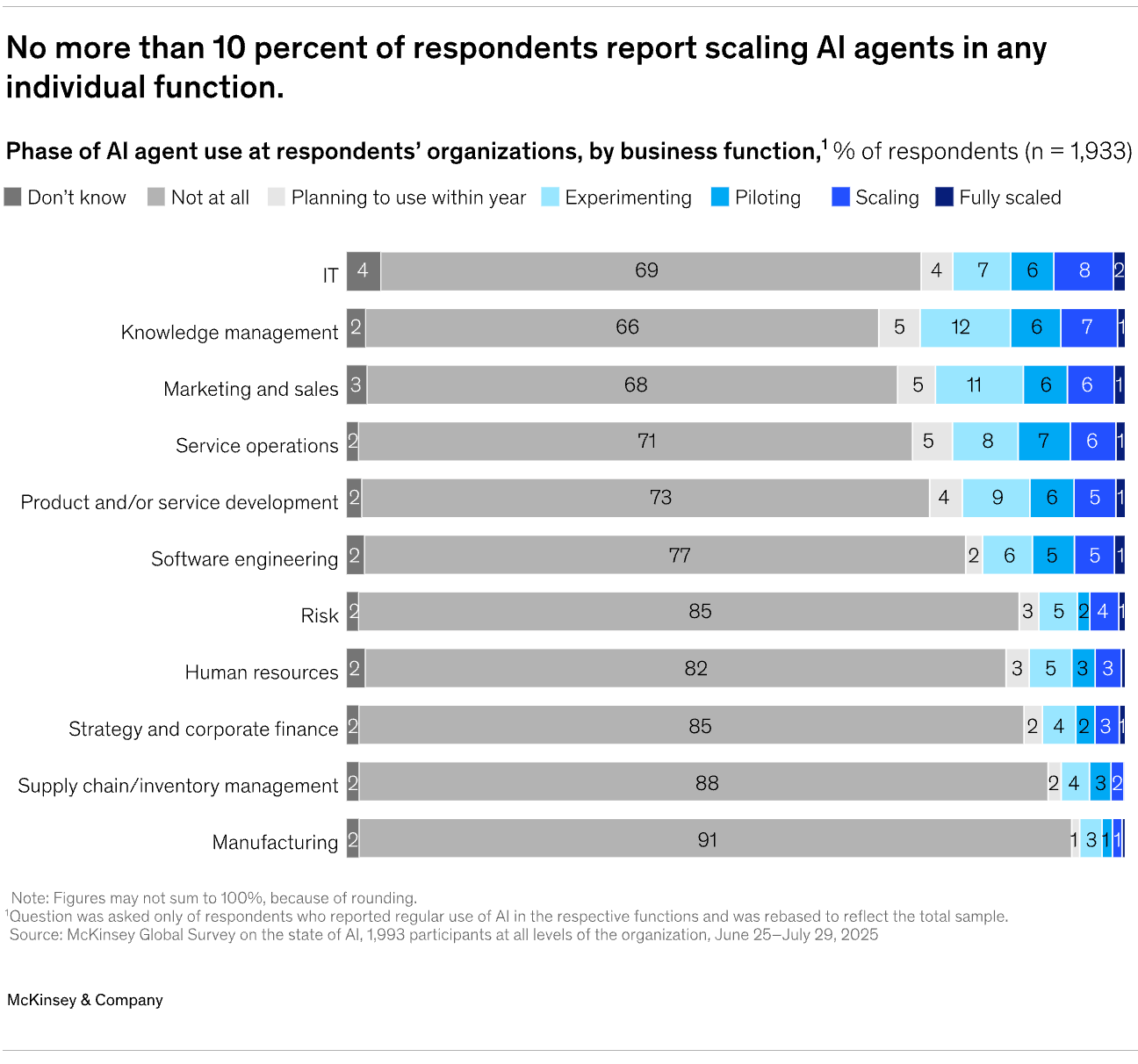

McKinsey – The State of AI: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai)

(Brynjolfsson & McAfee – The Second Machine Age: https://wwnorton.com/books/The-Second-Machine-Age/)

(OpenAI & cloud inference economics: https://openai.com/pricing)

(McKinsey – Economic potential of generative AI: https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/the-economic-potential-of-generative-ai)

(McKinsey – enterprise AI adoption data: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai)

(Google Cloud TPU overview: https://cloud.google.com/tpu/docs/intro-to-tpu)

https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/insights/blackrock-investment-institute/publications/outlook#global-investment-outlook

https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/policy-issues/artificial-intelligence.html

(Brynjolfsson & McAfee – The Second Machine Age: https://wwnorton.com/books/The-Second-Machine-Age/)

https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/digital.html

https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/agents-robots-and-us-skill-partnerships-in-the-age-of-ai?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/articles/013824/2015-02-11/#:~:text=Von%20der%20vorindustriellen%20Wirtschaft%20zur%20nachindustriellen%20Gesellschaft,-Die%20Schweiz%20im

https://www.nber.org/papers/w31815

https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Keynes.html; https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Sociology/Introduction_to_Sociology/Sociology_(Boundless)/08%3A_Global_Stratification_and_Inequality/8.05%3A_A_Comparative_Analysis_of_Global_Stratification_in_Mexico/8.5A%3A_Distribution_of_Wealth_and_Income#:~:text=An%20idea%20taken%20from%20Karl,totally%20equal%20distribution%20of%20wealth.